Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

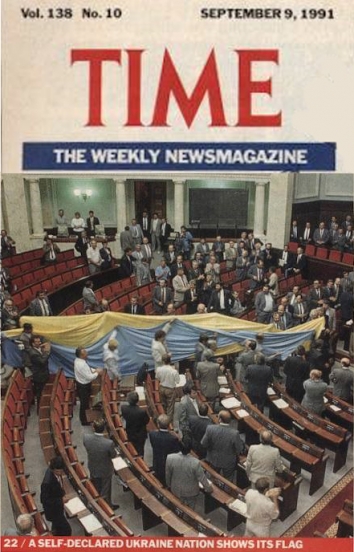

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

A BRIEF SUMMARY OF PIONEER HISTORY ON THE 90 anniversary

Produced by Robert A. Jarnigan

Produced by Robert A. Jarnigan

Reproduced with permission from The Iowan magazine, 1979.

Pubished by U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC),

Wash, D.C., Wed, Nov 9, 2016

In mid-summer, the corn stands chest-high in the experimental plots surrounding an ultra-modern research and testing station in a suburb just northwest of Des Moines. Almost daily, automobiles arrive to dispatch visitors from afar - from Mexico, Japan, the Far East - who've come to learn about "yellow gold," the food crop that is one of this country's prime nutritional resources.

The visitors come to Johnston, Iowa, the home for more than 50 years of what is now a worldwide agribusiness, Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Inc. For the fiscal year 1979, the company and its divisions grossed about $320 million, continuing to share its expertise and products with customers from all parts of the globe.

The firm's solid reputation rests largely upon foresight and groundwork of its founder, Henry Agard Wallace. A young editor at his family's agricultural magazine, Wallaces' Farmer, Wallace believed that the potential for increased corn yields lay in the direction of hybridization, or the inbreeding and crossing of different varieties of corn plants to produce a more healthy, durable stock.

Pioneer roots date back to 1926

In 1926, when Wallace, a future Secretary of Agriculture and Vice President of the United States during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt, formed what was then called the "Hi-Bred Corn Company" with a small group of Des Moines businessmen, the hybridization of corn was still in the laboratory stage. The common practice then was to have a farmer simply save seed from one year's crop and use it to plant the next.

Wallace looked beyond the common practice and in his youth perceived the possibility of improving corn production through the selected inbreeding of varieties. By the mid-1920s he had already experimented extensively with hybridization. He was convinced that growing corn from hybrid seed was the wave of the future and that there was a vast marketplace for the product once farmers could be convinced of its benefits.

Writing prophetically in Wallace's' Farmerin the mid-1920s, Wallace said, "No seed company, farmer or experiment station has any inbred seed or cross of inbred seed for sale today. The revolution has not come yet, but I am certain it will come within ten or fifteen years."

He did not miss the mark by much. At the beginning of World War II, 90 percent of the corn raised by farmers in the Corn Belt states was raised from hybrid seed.

Part of Wallace's mission was to improve the lot of the farmer, and he plunged into this endeavor with a hefty dose of enthusiasm. This enthusiasm was contagious. In 1925, a young farmer from Illinois talked corn half the night with Wallace in Des Moines. He was Lester Pfister, later to become a substantial grower of hybrid corn in Illinois.

Wallace received more than an adequate preparation for genetic work in agriculture. He was born into a family which included farmers and farm publication editors. His grandfather, Henry Wallace, affectionately known as "Uncle Henry" to thousands of Midwestern farmers, had been a minister in Winterset before ill health forced him to give up his pastorate and become a landowner in Adair County. Regaining his health, he turned to writing about farming, and soon purchased the Winterset Chronicle.The Chronicle became an outlet for such topics as stock breeding, crop rotation and soil conservation.

His son, Henry Cantwell Wallace, studied agriculture at what was then Iowa State College in Ames, and then turned to manage the family farm, where Henry A. was born on October 7, 1888. Henry C. returned to Ames with his family in the early 1890s to finish schooling. At the age of six, young Henry A. is said to have been already learning about plant breeding through visits with a botanist, George Washington Carver, then in residence on the Ames campus.

By the mid-1890s, Henry C., his brother, John P., and their father "Uncle Henry," had moved to Des Moines where they continued to publish a weekly paper, Wallace's' Farm and Dairy,acquired a few years before in Ames. Renamed Wallace's' Farmer, this publication would become in the 1920s the voice whereby Henry A. Wallace would tell the nation about his advancements in hybrid seed corn production.

The Original Side-By-Side: The Best and the Worst

All this was yet to come when, in 1903, Henry A. watched Professor Perry G. Holden of Iowa State judge a corn show. The young man asked Holden how he knew that the top 10 selected ears would produce more corn than the bottom-ranked 10 ears, if planted in a field. Henry's father suggested that Henry plant kernels from the "best" and "worst" samples side-by-side the following spring to see what would happen. The experiment took place at what is now a residential neighborhood in Des Moines, at 38th Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, on 10 acres of land that Henry’s father owned.

Professor Holden and the Wallaces were surprised to see the results when fall harvest came. The highest yield came from one of the samples Holden had judged among the worst, and the total yield of the top 10 samples was less than that of the bottom samples. From then on, Henry A. campaigned against "pretty ear" corn shows until they lost their significance in the 1930s.

From an early age young Henry exhibited a temperament well-suited for scientific and business endeavors. "He had a very inquiring, very retentive mind," recalls his younger brother, James W. Wallace, of Des Moines. "He wrote his first article for Wallaces' Farmer when he was 19 years old. He also made the most of an intellectual heritage from his father and a great religious belief inherited from his grandfather."

Following in the footsteps of his father, Henry A. attended Iowa State, graduated in 1910 as top man in the College of Agriculture, and immediately joined the staff of Wallaces' Farmer as a reporter. At college he had taken an interest in Dr. George Shull's pure-line corn breeding, a practice which stimulated his own ideas for corn variety improvement. In 1913 he produced his first hybrid in his own backyard garden in Des Moines, starting a course of experimentation that eventually led to the establishment of a hybrid seed corn company 13 years later.

Wallace’s initial hybrid results were not encouraging. They convinced him that his methods of breeding were too cumbersome and costly to be practical for farmers.

Early Frustrations

His road to success was long and arduous. Russell Lord has written about the setbacks and failures in The Wallaces of Iowa.

He (Henry A. Wallace) grew in all nearly three hundred crosses of the standard North American strains, with strange intermixtures of strains from Russia, Australia, Hungary, China and Argentina. Most of the crosses proved worthless, but all that showed any promise in point of yield, vigor, earliness, resistance to disease, or adaptability to impoverished soils were tested for a second year or longer.

1' Russell Lord,THE WALLACES OF IOWA (Boston-Houghton Mifflin Company, 1947), P. 185.

Wallace himself wrote of the frustrations in an article which appeared in Wallaces' Farmer in March 1919. In reference to what had first seemed to be a successful cross between "Boone County White" and "Silver King," Wallace lamented,

In spite of all our selection, it got poorer and poorer. About one in every ten of the young plants as they came up in the spring would have white leaves, and of course the albinos died before they were three weeks old. About one in every fifteen ears was a freak, having a cluster of four or five nubbins without kernels at the place where there should be one good ear. I saw that I was fooling away my time with this cross.

Undiscouraged, Henry A. followed the lead of an early corn researcher, Donald Jones of the Connecticut Agriculture Experiment Station, and made single crosses in the summer of 1919, using East and Hayes inbreds from the Connecticut station and some inbreds out of Hogue's Yellow Dent of the Nebraska station.

About this time, he needed more land for his research, and persuaded his wife, Ilo, to trade property she had inherited in Warren County for 40 acres of sandy loam near the village of Johnston, northwest of Des Moines. He planted his first plots at the Johnston site in 1920, including among his inbred choices a copper-colored Chinese variety named Bloody Butcher.

The following two years Henry A. entered hybrids in the Iowa Corn Yield Test at Iowa State, and a single cross that he had named "Copper Cross" won in 1924 as the highest yielding variety in south-central Iowa. It was also the first hybrid developed in the Corn Belt to be bought for planting. Copper Cross sold that year for one dollar a pound, or at the rate of $56 per bushel.

Wallace's Copper Cross

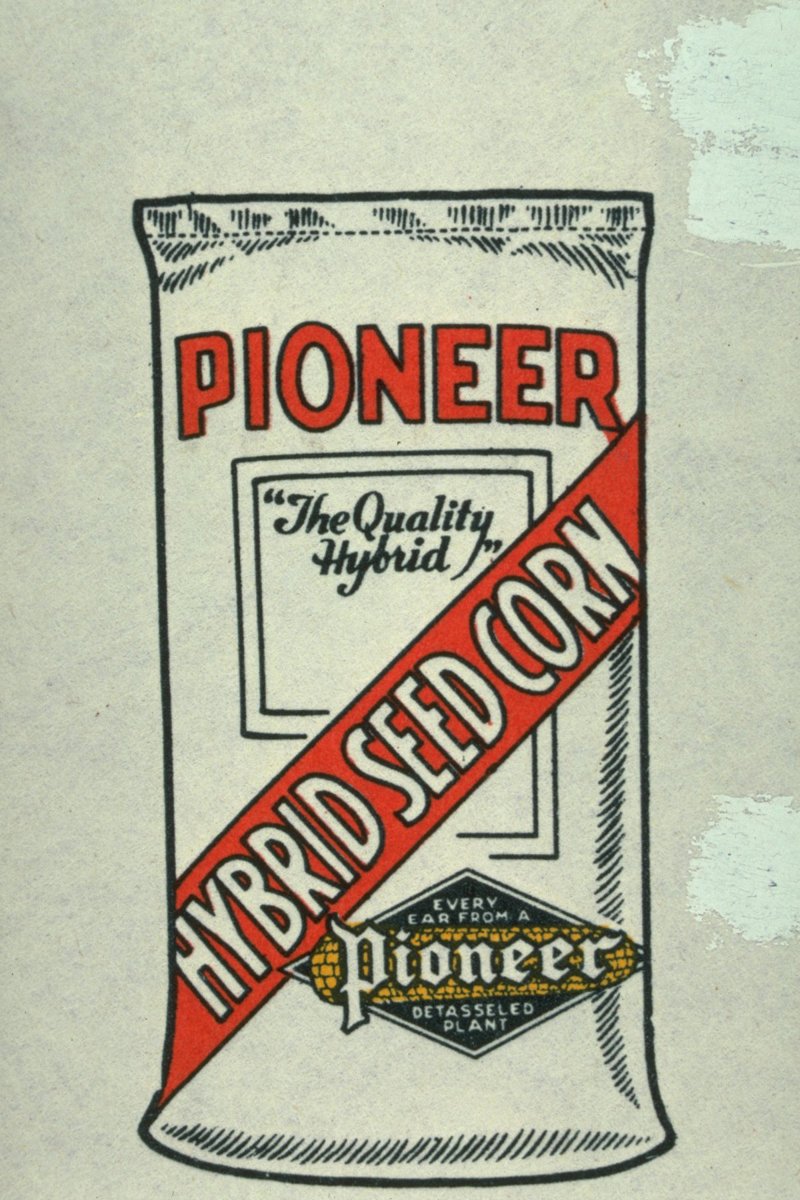

Meanwhile, advertising was bringing hybrid corn to the attention of more and more Americans. The Iowa Seed Company placed an ad about Wallace's Copper Cross in its Spring 1924 catalog. Henry A. Wallace wrote the copy, which appeared under the heading: "Copper Cross, An Astonishing Product Produces Astonishing Results."

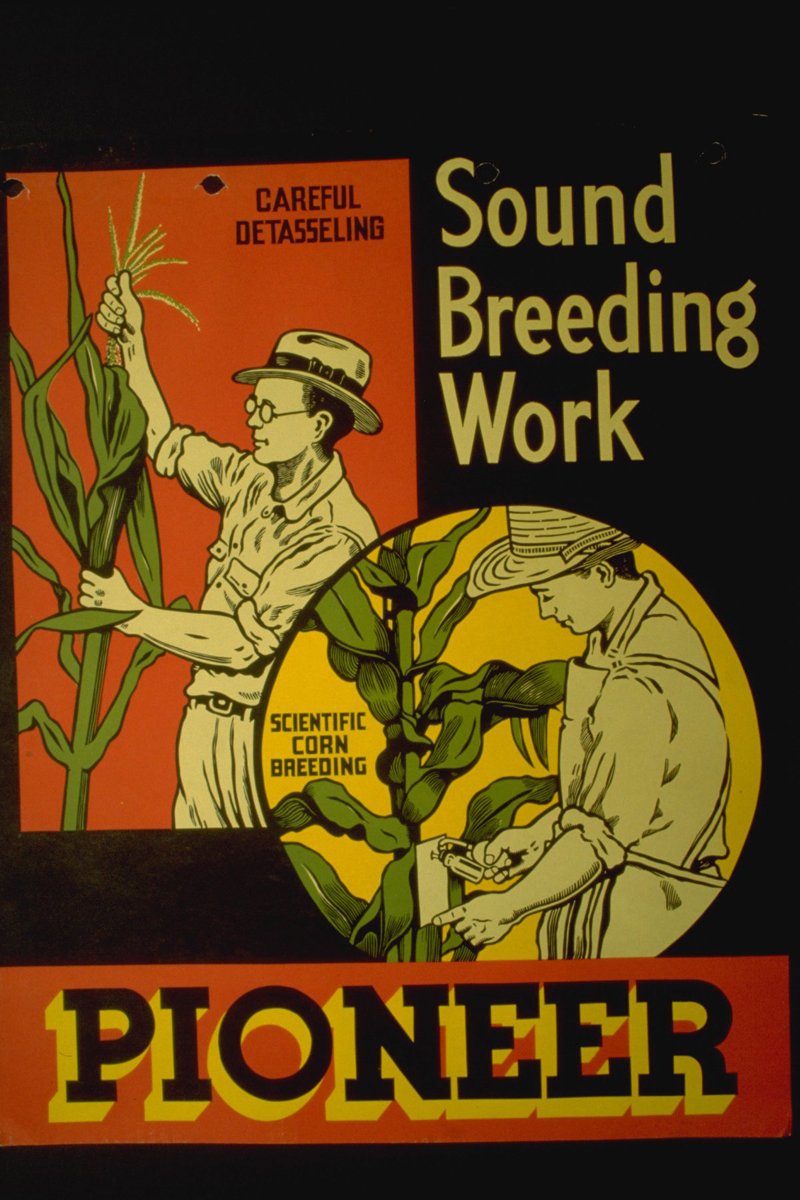

Wallace's relationship to the Iowa Seed Company had been formed through a friendship with one of its employees, George Kurtzweil, who opened the door to hybrid seed corn production at the family farm in Altoona. Kurtzweil's sister Ruth spent one summer on the farm detasseling corn in a one-acre plot, and in later years liked to recall that she once detasseled single-handedly all the hybrid seed corn production fields in the state.

Despite Copper Cross' early flurry of success, the high cost of the seed and poor condition of its parent ears kept the variety from being widely used, and it was soon discontinued.

As Wallace added to his Johnston acreage, the vast number of inbred lines he collected for experiments with single and double crosses soon became burdensome. He was also spending more time as nationwide spokesman and consultant in hybrid corn production, traveling afar to convince people of his ideas, and inspecting various corn breeding experiments across the country.

To discharge himself of some of these mounting duties, Wallace invited J. J. Newlin, a young livestock advertising salesman for Wallaces' Farmer, to manage the burgeoning Johnston farm. Newlin became first in a line of longtime Pioneer associates, and managed the production farm until his retirement in 1968.

As interest in hybrid corn production grew, Wallace began to realize that his original idea of having farmers make their own crosses was much too complicated. He first considered forming a national organization that might conduct breeding work and aid farmers in developing inbred lines. Finally, however, he decided that inbreeding was a task for a highly specialized organization.

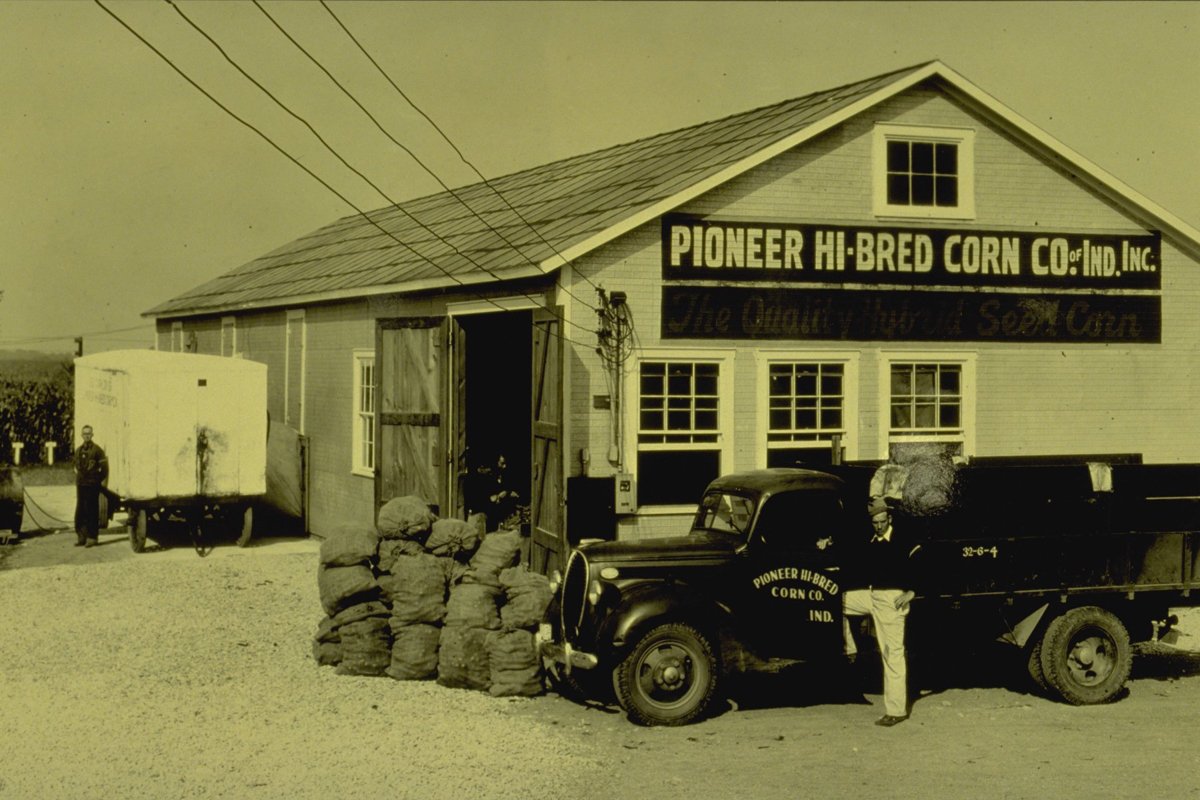

In 1926, Henry A. Wallace organized the first company exclusively devoted to developing, producing and distributing hybrid seed corn. Henry suggested the name "Hi-Bred Corn Company" for the venture. In the mid 1930s, "Pioneer" was added to the title to distinguish it from other hybrid corn companies that had sprung up elsewhere.

An initial shareholders meeting was held in Des Moines in the spring of 1926. Among those present were Henry A. Wallace, his brother, James W. Wallace, Fred Lehmann, J. J. Newlin, Simon Casady Jr. and George Kurtzweil. Henry was elected president; Newlin, vice- president; Casady, treasurer; and Jim Wallace, secretary. Of this original group, only Jim Wallace is still living. Wallace, a member of the board of directors at Pioneer from 1926 until his retirement in 1969, has held every elective office in the company. He was president of Pioneer from 1956 to 1965, chairman of the board from 1965 to 1969 and is now honorary chairman of the board.

During its first year, the newly-established company produced 1,000 bushels of seed and sold 650 bushels, starting out on a course of growth that has continued unabated for more than half a century.

Recruting and Hiring Talent

In the late 1920s,the company, in pursuit of better inbred lines, began to recruit research talent. Raymond Baker, a young Ringgold County farmer who had shown an interest in hybrid corn in his agronomy classes at Iowa State, offered to produce and test Wallace's experimental hybrids. He was given samples to make experimental crosses on his farm. Baker entered three of his samples in an Iowa corn yield test, and all won honors. This convinced him to join Pioneer. From these beginnings, Baker worked his way from farmhand to chief of corn research for Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Inc.

Another contributor to Pioneer's early growth was a young Guthrie County farmer, Perry Collins. Collins, like Raymond Baker, was deeply impressed with the success of Wallace hybrids in the yield test. Collins grew some of the best hybrid combinations, and soon Baker asked Collins to join him in corn-breeding research being conducted at the Johnston facility.

The depression years were challenging for the fledgling company. Drought conditions of the mid-1930s both hindered and helped the development of hybrid varieties. For example, Perry Collins, working with experimental plots in northern Iowa's Pocahontas County, found that some varieties did not survive the severe drought of 1934.Those which did, he saved and planted the following year. This proved to be a wise decision, for in 1936 - another drought year - these outperformed open-pollinated corn. With evidence such as this, the demand for the new hybrid corn swelled.

As demand grew, so did the need for more assistants. Within months after Perry Collins got his start at Pioneer, Nelson Urban, a 1929 graduate of Antioch College in Ohio, was hired as business manager. Urban had previously worked in the printing department at Wallaces' Farmer.When the depression ended Urban's printing job, Wallace asked the young man to join the Pioneer company. Urban worked first as bookkeeper and supervisor of detasseling work at Johnston, then turned to the activity which he directed throughout his Pioneer career - selling.

Selling any type of corn during the Depression, particularly the then largely-unfamiliar hybrid varieties, was a difficult task. The salesman first had to explain to the farmer the nature of hybrid corn, and then convince him to buy several bushels. Urban later recalled, "The only way they (farmers) were really sold was to get them to take an eight-pound sample, put it up against their own open- pollinated varieties, and rub their noses in the results."

Farmers were quick to recognize the advantages of the new selections. Hybrid plants grew upright, unlike the weaker, open-pollinated corns of the time. (Farmers appreciated not having to engage in the back-breaking chore of picking up fallen ears off the ground.) High yields also came with the heartiness of hybrid varieties. Farmers benefited from the extra 10 bushels per acre that the hybrids produced. All this made the selling task easier.

A Half Century Later

In 1926, the newly-organized Hi-Bred Corn Company at Johnston sold 650 bushels of hybrid seed corn out of a total production of 1,000 bushels. Today, Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Inc., commands a worldwide market, with net sales for the fiscal year ending August 31, 1979, estimated at $320 million. Of this figure, approximately $250 million, or 78 percent, represents income on the sale of hybrid seed corn. In 1979, farmers in this country planted just under 80 million acres of corn, using about 21 million bags of seed corn. Sales of Pioneer hybrid seed corn for this same year amounted to over 6.2 million bags, or about 30 percent of the United States market. In 1978, more than 600 farmers in this country produced Pioneer brand seed corn on approximately 237,000 acres, to be sold in 1979. While the company offers more than 115 corn hybrids in North America, the 10 largest volume hybrids account for about 63 percent of total sales. Pioneer's extensive operation includes research facilities in 18 states, Canada, Jamaica, India, France, Brazil and the Philippines. The company's products are sold in approximately 90 countries.

One of the early Pioneer salesman was Roswell "Bob" Garst who during the Cold War years of the 1950s gained world-wide attention for his agricultural dealings with Khrushchev's Russia. A longtime friend of Henry A. Wallace, Garst was selling real estate in Des Moines when the Depression struck. He returned to his hometown of Coon Rapids with an agreement to sell Pioneer seed corn in western Iowa and soon entered a partnership with Charles Thomas, a local businessman. Together they founded the Garst and Thomas Hybrid Seed Corn Company in 1930. Operated as a separate entity, the Garst and Thomas enterprise, then as now, buys its parent stock from Pioneer, and pays the Des Moines based firm a royalty for its gross sales.

To spread the gospel of hybrid corn, Nelson Urban organized an innovative farmer-salesmen network, a system still in practice at Pioneer today. Urban believed the most convincing salesmen for the product were the users themselves, and he and Garst encouraged Iowa farmers to sell seed corn.

About setting the standards for hiring farmer-salesmen, Urban recalls, "What I was looking for first was a very reliable person. If he wasn't reliable and didn't have good standing in the community, I didn't want him."

By the end of the 1930s, Pioneer had expanded its corn selling activities into Minnesota and South Dakota and eastward into Illinois, Indiana and Ohio. By World War II, Pioneer was one of the leading suppliers of hybrid seed corn in the country.

The 1930's: Changes at Pioneer

Pioneer had undergone major organizational changes in 1933. That year, Henry A. Wallace accepted President Franklin D. Roosevelt's invitation to serve as Secretary of Agriculture. With Wallace's departure, his close friend and legal advisor, Fred W. Lehmann, Jr., became Pioneer's second president. With Lehmann as head, Jim Wallace became executive vice-president and general manager, J. J. Newlin took charge of seed production, Nelson Urban was named vice president in charge of sales, and Raymond Baker continued to supervise the expanding research program.

The company prospered, guided by Lehmann's sound instincts for business. He is generally regarded as the man who developed a working philosophy for the company. Says Raymond Baker, "Lehmann realized people appreciated and paid for quality. He always said, 'A quality product is more important that getting maximum business.' Lehmann's theory was that if you told the farmer everything

about your hybrid, the good and the bad, you might not sell as much corn but would gain complete confidence in the product and the company." Lehmann seldom visited the production areas, but always gave Baker's research programs full financial support.

As had been the case under Wallace, Pioneer continued to court new talent. One newcomer was R. Wayne Skidmore, who was hired "to mind the store" at the Johnston office. A graduate of Drake University in accounting, Skidmore first worked on a part-time basis, delivering milk to area farmers in the morning and keeping the Pioneer books in the afternoon. In time he became office manager, and in 1949 was named sales manager for the Minnesota-South Dakota-Iowa area. Skidmore became the company's fourth president in 1965, and during his eight years as head, continued to refine the farmer-salesmen program established by Urban and Garst.

Another newcomer who came to Pioneer in the early 1930s was James Weatherspoon, a young plant breeder from Oregon. His specialty was disease-control, an area which by this time was commanding more attention from the research department at Johnston.

One of Weatherspoon's chief accomplishments during his more than 40 years at Pioneer was the design of the company's corn yield test program. Largely through Weatherspoon's efforts, Pioneer began using electronic data processing in the 1950s to analyze test results.

The current chairman of Pioneer, Dr. William L. Brown, began his association with the firm in the 1940s, as a member of its corn breeding staff. Through his work there, he had become one of the country's leading agricultural geneticists.

The 1960's: Global Expansion

Brown and Skidmore shared with others at Pioneer a deep interest in improving world food supplies, and believed the company should apply its genetic expertise at every opportunity. This sense of worldwide mission led Pioneer to greatly expand its foreign operations in the 1960s.

Says Dr. Brown today, "I have no doubt at all about the long-term need for greater productivity and efficiency in agriculture; population growth and increasing affluence in many of the developed countries are going to increase the demand for food in the foreseeable future."

The tradition of improving plants and livestock by applying well-tested genetic principles continues at Pioneer. Today, laboratory technicians experiment with a variety of crops besides corn - alfalfa, wheat, cotton, sorghum and soybeans. This research plus a sophisticated marketing system means that farmers are receiving the proper seed for their particular climate, soil or terrain.

A recent venture for Pioneer is its Microbial Products division, acquired in April 1977, and headquartered in Portland, Oregon. Its specialty is the isolation and multiplication of selected bacteria to perform specific tasks, This new form of agricultural technology represents a possible course for disease and insect control. In recent years, man-made pesticides have become more costly and threatening to the environment. Research has indicated that microbial cultures may be more effective than present man-made chemicals; thus it is possible that farmers may soon be turning to Pioneer-brand bacterial cultures for crop protection.

Programs such as this continue the Wallace tradition of service to agriculture which perhaps reached its finest expression in Henry A. Wallace's development of hybrid corn.

Today in Pioneer's headquarters on Mulberry Street in downtown Des Moines there is a Grant Wood portrait of Henry A. Wallace overlooking the main reception area. It was drawn midway through his lifetime, long after the days of his experimental backyard plantings.

Now, the world serves as laboratory for this company which had its origins in suburban soils near Des Moines. Last modified 11/6/2014 5:26 PM

Contact: Tesar, Deb S.