Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

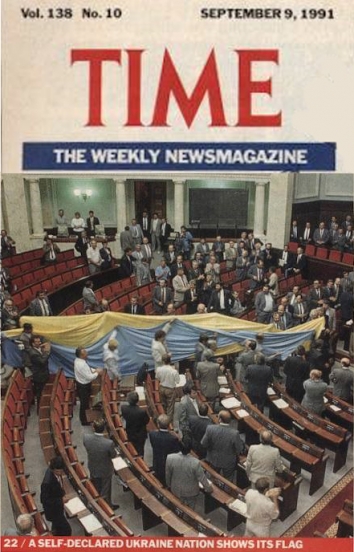

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Report Launch: The Black Sea… or a Black Hole

The Black Sea … or a Black Hole? by LTG (Ret.) Ben Hodges, Pershing Chair in Strategic Studies at the Center for European Policy Analysis. Jan 22, Fri, 2020

The Black Sea … or a Black Hole? by LTG (Ret.) Ben Hodges, Pershing Chair in Strategic Studies at the Center for European Policy Analysis. Jan 22, Fri, 2020

“What happens in the Black Sea doesn’t stay in the Black Sea,” Tihomir Stoytchev, Bulgaria’s ambassador to the United States

“What happens in the Black Sea doesn’t stay in the Black Sea,” Tihomir Stoytchev, Bulgaria’s ambassador to the United States

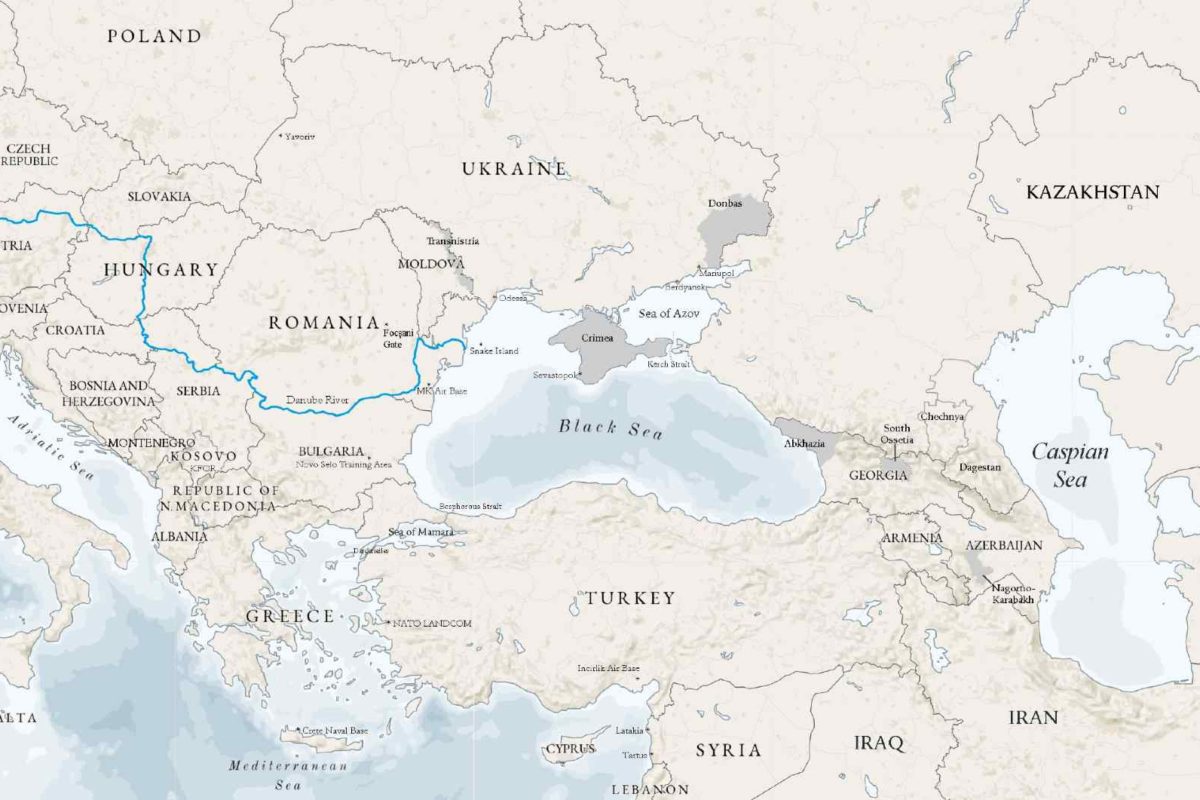

The Black Sea region (BSR) is where Russia, Europe, the Middle East, the Balkans, and the Caucasus come together. The region is at the center of four great forces:

- Democracy on its western edge

- Russian military aggression to its north

- Chinese financial aggression to its east

- Instability in the Middle East to its south

The BSR is, in short, the literal and philosophical frontier between liberal democracy and autocracy. It matters to the West and to the Kremlin. But U.S. and Western strategy in the region has been insufficient. Great-power competition prevented great-power conflict. Conversely, failure to compete and to demonstrate and protect interests, in all domains, can lead to power vacuums and misunderstandings that can, in turn, lead to an escalation of tensions and actual conflict.

Russia uses its new generation (or “hybrid”) warfare to force NATO into an asymmetric contest, thus avoiding many of the Alliance’s greatest strengths. Challenging the Kremlin with military means only, in its perceived sphere of influence, reveals our lack of an effective long-term strategy, potentially leading to an escalation where Russian President Vladimir Putin’s regime holds most of the cards.

We need greater focus, vision, and willpower. This region must now be where NATO and the West compete: holding the line against anti-democratic forces, taking the initiative, establishing our influence, and protecting our strategic interests.

Why the Black Sea Region Matters to the Kremlin

Russia’s concerns are aggressive, but also defensive. It fears growing Western and, in particular, Turkish influence in the BSR, which could turn the Black Sea into a “NATO lake.”1 Moscow wants to ensure that no new east-west energy corridor can bypass Russia or weaken its grip on oil and gas exports. The BSR is Russia’s key strategic maritime domain now and into the future. Russia believes it can operate with near impunity in the BSR, building and then projecting capabilities into the Caucasus, the Balkans, the Middle East, and beyond. The Kremlin’s growing military capabilities in the BSR have, in effect, surrounded Turkey, while enabling Russian naval operations in the Eastern Mediterranean and its support for Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria and Gen. Khalifa Haftar, the commander of the self-styled Libyan National Army, in Libya.2 These Kremlin actions have also “weaponized” refugees, particularly from Syria, with a huge negative impact on European cohesion and budgets.3

The Kremlin is prepared to use force in the BSR. Since 1992, it has backed the separatist authorities in the Moldovan region of Transnistria. It invaded Georgia in 2008 and continues to occupy 20% of Georgia’s sovereign territory (Abkhazia and South Ossetia).4 It occupied Crimea in 2014. It seized three Ukrainian naval vessels in November 2018.5 It continues to support and lead separatist forces in Donbas while preventing the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) from fulfilling its monitoring tasks.6

Russia’s illegitimate claims to territorial waters around Crimea also threaten Ukrainian gas fields in the western Black Sea and Romania’s Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs).7 A claimed “humanitarian crisis” in Crimea due to water shortages could be a pretext for military action. The logistical and infrastructure legacy of the Russian Kavkaz-2020 military exercise, which ended in September, remains in place and available for use in subsequent weeks and months.8

So, What Do We Do?

On the other side of the continent, the Baltic Sea has enjoyed considerable attention from Western security planners over the past 20 years, resulting in a substantial improvement in regional security. It is now time to close the security gap in the BSR.

We need to shape events through military alliances, diplomacy, private investment, and effective deterrence instead of reacting to or ignoring or accepting Kremlin coercion and other interventions. This is entirely feasible. Doom-laden talk about the end of U.S. strategic interest in Europe is overblown. U.S. attention is shifting toward the Indo-Pacific region, but its national interests depend significantly on stability, security, and prosperity in Europe. European allies are uniquely close and effective. NATO is the most successful military alliance in modern history and remains the mainstay of U.S. security efforts not only in Europe, but also in the Middle East and Africa.

The West needs to change the rules of the game, develop its own approach to hybrid warfare, use all the tools of national and alliance power, and compete across all four domains of the DIME (Diplomacy, Information, Military, and Economic) framework.

.png)

Photo: Joint exercises of the Northern and Black Sea fleets. With Commander-in-Chief of the Navy Nikolai Yevmenov, centre, and Commander of the Southern Military District Forces Alexander Dvornikov.

Credit: Kremlin

1. Diplomacy

The aim should be to build diplomatic consensus between like-minded players about the strategic importance of the greater BSR, while communicating our intentions clearly to the Kremlin. Black Sea nations need to put their voices together in cooperation with diplomatic efforts in Washington, Brussels, Berlin, London, and Paris to draw attention to the BSR and highlight its strategic importance.

Successful templates include the concerted efforts by Central European and Baltic countries in the run-up to decisions on European Union (EU) and NATO expansion in the 1990s and early 2000s and the decision at the NATO Summit in Warsaw in 2016 to deploy Enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) battle groups to Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland.9

German leadership is key. Its rotational seat on the U.N. Security Council and current seat on the U.N. Sanctions Committee, as well as its role (in the second half of 2020) as president of the Council of the European Union, give it leverage and a platform. The immediate goal of BSR-focused diplomacy should be to reject any and all claims to legitimize the Kremlin’s illegal annexation and occupation of Crimea. In particular, Russia should not be allowed to promote creeping legalization of its land grab over time, for example, by exploring or developing gas fields around Crimea or by using force to stop Ukrainian naval vessels off the coast of Crimea.

This should include an international boycott of any ships sailing directly from Crimean ports. They should be turned away from Western ports and denied maritime insurance. Russian pressure within the London-based International Maritime Organization (IMO) has unfortunately, so far, limited visibility of these violations and hence the effectiveness of these efforts.

More broadly, BSR diplomatic efforts should review and, if necessary, expand/extend existing sanctions. An international monitoring and sanctions compliance regime, which highlights violations of sanctions in international media and organizations, should be established. Despite sanctions hundreds of vessels sail in and out of Crimea each year, often turning off their mandatory tracking devices, changing flags, and using various other methods to avoid restrictions.10 Vessels from several European nations have been involved in side-stepping sanctions.11 Sanctions should be extended to businesses that use Crimean ports, not just the vessels themselves.

Sanctions should target oligarchs close to Putin, who depends on their financial resources, in an effort to weaken that support. Measures should include travel and study bans on oligarchs and their immediate family members — for example, they should be barred from schooling or purchasing real estate in the United States or the United Kingdom. BSR nations should follow up on sanctions protocols rather than leaving enforcement to EU member states.

Combining such efforts would apply broader pressure on the Kremlin to live up to its international obligations and agreements and act responsibly.

BSR diplomacy should also condemn and restrict Russia’s frequent live-fire training exercises that periodically block large segments of the Black Sea, impairing freedom of navigation.

Secondary BSR diplomatic priorities include:

- Resolving the dispute between Serbia and Kosovo over the latter’s recognition as an independent state. The Western Balkans are the backdoor of the BSR. The United States should work with the EU to ensure continued Western integration of Serbia and the rest of the Balkans. NATO should also continue its KFOR (Kosovo Force) peacekeeping mission in the Balkans.

- Addressing Hungary’s issues with Ukraine. Failure to do so limits NATO’s ability to work more closely with Ukraine, affecting, in turn, the security and stability of the greater BSR.

Time for Turkey-U.S.-NATO 2.0

The most important long-term diplomatic goal is stabilizing and strengthening the relationship between Turkey and the West, and, specifically, between Turkey and the United States. Failure to do so risks further cracks in NATO cohesion in one of the most geographically strategically important parts of the Alliance — cracks which are already being exploited by the Kremlin.

The EU’s prioritization of Greek and Cypriot concerns risks further alienating Turkey within the transatlantic community, including in the Black Sea. Policymakers in Washington and Brussels must find a way to embrace Turkey as the strategic pivot linking the Black Sea, Levant, and North Africa and as a major regional power that is at the crossroads of several regions and challenges. Turkey is essential for deterrence in the Black Sea as well as a critical bulwark against the Islamic State group and Iran. Protecting all of this must be a priority.

Turkish geostrategic thinkers and planners know that the Black Sea has been an historical vulnerability for them for centuries. Turkey has fought more wars with Russia in its history than any other opponent, and without much success.

Turkey would like to do more to advance NATO's interests in the Black Sea, but it is distrustful of the willingness of the United States and the rest of NATO to come to its defense if it does in fact push back firmly against the Kremlin. The United States should make clear that it would stand with Turkey in such a case.

Additionally, the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh puts a lot of pressure on the Ankara-Moscow relationship. Turkey supports the Azeris while the Kremlin, which sells weapons to both sides, has bases in Armenia. The United States should make clear to Ankara that while it doesn’t support an expansion of the conflict, it will support Turkey if there is a problem with Moscow.

Photo: Turkey's drilling vessel Kanuni departs on her maiden trip to the Black Sea in Istanbul, Turkey November 13, 2020. Credit: REUTERS/Yoruk Isik

The United States should also cease providing weapons to the Kurdish YPG militia, recognize that Turkey has legitimate internal security concerns regarding the Gülenists, and find a way to resolve the current legal impasse regarding the extradition of their U.S.-based leader, Fethullah Gülen.

Western countries should recognize that Turkey is on the front line of the Middle Eastern refugee crisis, with more than 3.5 million refugees in Turkey or on its border with Syria.

The United States should reframe structures dating from the Cold War, including changing the EUCOM/CENTCOM and Department of State regional boundaries, which currently sit on the Turkish-Syrian border, to one that is more mindful of Turkey’s strategic situation.

The United States should offer Turkey a way out from its misguided purchase of Russian S-400 air defense systems. It should consider making a special case for Patriot sales to Turkey that include technology transfer and co-development with the Turkish defense industry, similar to the arrangement for F-35 production and then bring Turkey back into the F-35 program. However, Turkey’s current testing of the S-400 system on the Black Sea coast makes this increasingly difficult.

The Turkey-Greece conflict over drilling for gas in the Eastern Mediterranean should be resolved. Germany should lead this diplomatic effort, with strong U.S. and U.K. support.

Offer to support the construction of the proposed Istanbul Canal, not for the purpose of evading the Montreux Convention, but to improve the economic potential of the BSR, assuming Turkey is able to adequately address environmental concerns. Western investors should make this offer before China or Russia offer to do it.

2. Information

Besides criticizing Russian actions in Crimea and elsewhere, we should accentuate the positive. The West has a better story to tell, winning the hearts and minds of citizens through the ideals of individual empowerment and dignity. But we must live up to our own ideals and tell that story better. Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has reduced its investment in cultural influence, weakening the kinship Eastern Europeans feel toward the United States and the transatlantic relationship. However, technology offers huge opportunities to rekindle the U.S. ideal, and the BSR is a perfect place to start. We need to support independent media as well as U.S. government-supported news outlets like Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and Voice of America. The Russians and Chinese are much more deliberate about directing resources.

We also need to revive our education programs. In the past, some of the most effective U.S. influences have been the schools built by U.S. initiatives, especially schools that taught the basic principles of parliamentary and U.S. democracies: direct representation, checks and balances, decentralization, and judicial independence. U.S.-sponsored and affiliated universities, high schools, and other programs offer great potential for the competitive exercise of U.S. soft power.

From 1992-2013, the U.S. Congress made available hundreds of millions of dollars via the Edmund S. Muskie Graduate Fellowship Program to provide U.S. graduate-level education to the 25-35-year-old demographic in the states of the former Soviet Union. Now, the graduates of these programs — “Muskies,” as they call themselves — are ministers and deputy ministers and have an understanding of the United States and a transatlantic view. We should reinvigorate the Muskie Program or develop a successor as a long-term investment in the region.

Montreux Convention: This treaty gives Turkey sovereignty over the so-called Turkish Straits (the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles) and governs naval presence in the Black Sea. Submarines based in the Black Sea are allowed to transit the straits only for purposes of repair.12 Russia has breached this rule by sending a submarine from its Black Sea Fleet to take part in operations in the Eastern Mediterranean.13 We should ensure Turkey is holding the Kremlin accountable for any violations. A public information device, perhaps something similar to a virtual “Times Square” billboard display, could display violations.

3. Military

The BSR is essential to Western security and stability. Western defense planners need to make the region a higher priority and invest more resources. The Russian Black Sea Fleet will always have a numerical advantage, as a result of the Montreux Convention, so the Alliance must find innovative ways to gain the initiative.

The Alliance must develop a strategy that places the BSR in the middle of the geostrategic map. This strategy should be underpinned by a Graduated Response Plan (GRP), similar to what has already been accomplished in the Baltic region. Such a strategy and GRP will drive planning, resources, exercises, and presence to deter Kremlin aggression and provide a bulwark against Iranian and Chinese inroads.

Unlike in the Baltic Sea, attaining “sea control” in the Black Sea is not feasible, at least not in the early stages of a potential crisis, given the numerical advantage of the Russian Black Sea Fleet over combined NATO and partner naval capacities in the region.14 However, achieving “sea denial” so that the Russian Black Sea Fleet is unable to enjoy complete freedom of navigation and maneuver is feasible.

Ideally, Turkey should be NATO’s center of gravity in the region. Given its strategically decisive location and sizeable military capabilities it should lead deterrence efforts against the Kremlin. Turkey, however, is focused on its southern border and the Eastern Mediterranean.15 It is reluctant to challenge the Kremlin or disrupt the status quo in the BSR.

In the short to medium term, NATO should, therefore, designate Romania as its center of gravity due to its geographic location, proximity to other allies as well as Ukraine and Moldova, its robust modernization efforts, and its strategic transportation infrastructure. Accordingly, Romania should create its own anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capability to protect its coast and EEZ using standoff weapons such as anti-ship missiles, HIMARS (long-range rocket system), attack helicopters, Maritime Unmanned Systems (MUS), and armed unmanned aircraft systems (UAS, also known as drones).16

Romania should also offer to establish and host a NATO Center of Excellence for Unmanned Systems due to its ideal flying conditions and long Black Sea coastline as well as presence of the Danube River. Finally, Romania should continue to expand the training and logistics infrastructure at Mikhail Kogălniceanu Air Base (MK) and at the Smârdan and Cincu training areas, improving capabilities for joint, multinational live fire exercises that enable training that meets U.S. Army and U.S. Air Force qualification standards.

Read more: https://cepa.org/the-black-sea-or-a-black-hole/