Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

THE IMPACT OF THE UKRAINE CRISIS

Even if Russia does not invade Ukraine in early 2022, Vladimir Putin has succeeded, once again, in wreaking havoc on the already fragile Ukrainian economy.

Even if Russia does not invade Ukraine in early 2022, Vladimir Putin has succeeded, once again, in wreaking havoc on the already fragile Ukrainian economy.

By Sebastian Shehadi and Jon Whiteaker

Investment Monitor, Jan 31, 2022, updated Feb 12, 2022

A military instructor stands next to wooden replicas of Kalashnikov rifles, as civilians take part in a conflict training session in Kyiv and the world awaits Russia's next move. (Photo by Sergei Supinsky/AFP via Getty Images)

The first weeks of 2022 have seen the rapid build-up of tens of thousands of Russian troops on Ukraine’s borders, stoking fears of an invasion. While Russia denies it is planning an attack, US President Joe Biden believes that there is a “distinct possibility that the Russians could invade Ukraine in February”, according to a recent announcement from the White House.

It is important to remember that Moscow already invaded Ukraine back in 2014, when it annexed the country’s southern Crimea peninsula. Immediately after, it backed pro-Russian rebels who seized large swathes of the country’s eastern Donbas region, which they retain control of to this day. Some 14,000 people died in the fighting, while the Ukrainian economy never fully recovered.

Adding to this misery is the fact that, just when Ukraine’s markets began showing signs of vigour in more recent years, Covid-19 hit, which is coupled now with the threat of yet another Russian attack.

Ukraine economy has been in limbo for years

While the Ukraine crisis has not made significant international headlines since the 2014 war, its impact has very much lived on.

“We have been living in a state of frozen conflict since 2014 and entrepreneurs have become used to survival,” says Helen Shapovalova of Pan Ukraine, a Ukrainian tour operator. “[For example], after Crimea’s annexation we diversified and started the promotion of other tourist attractions of Ukraine.”

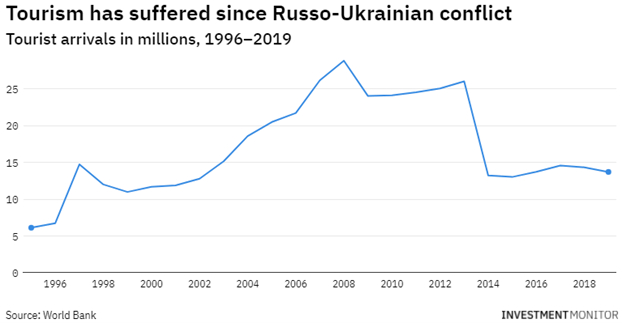

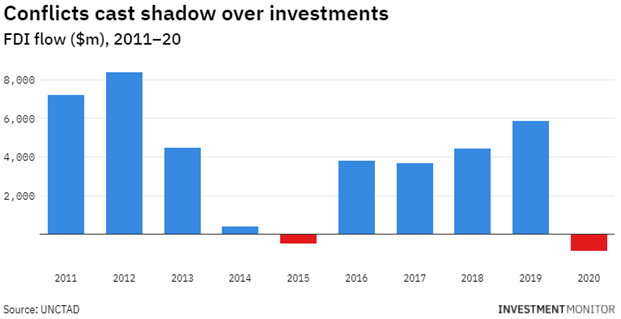

However, figures from the World Bank show that tourist arrivals to Ukraine have never recovered, cut in two compared with what they used to be. Foreign direct investment, while faring better than tourism, has also failed to rejuvenate since 2014 – as shown in the below chart.

“For eight years we have been struggling to attract foreign capital,” says Vasyl Myroshnychenko, CEO of strategic communications and government relations company CFC Big Ideas and a co-founder of the Ukraine Crisis Media Center. “Yes, we have some investments, but we could have had much more, and under today’s circumstances it is a no-go.”

Myroshnychenko believes that this has always been part of Putin’s strategy. “[He] keeps Ukraine unattractive to international investors,” he says.

That foreign investment has been withheld is particularly evident in the case of Chinese investors. “So many ventures from China have been put on hold since 2014,” says Yuri Bender, an expert on Ukraine and a magazine editor at the Financial Times Group. “If that Chinese money came in as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, it could really transform Ukraine’s infrastructure and ports.” Many believe that the Chinese are waiting to see if, and where, the Russians invade, not least since Ukraine’s coast is a very plausible target.

Where would Russia invade (if at all)?

For months, the White House has warned that Russia may invade Ukraine. This threat is very real but not, according to some experts, particularly likely.

“I don’t think we are at the stage of major war breaking out,” says Maximilian Hess, fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. “In fact, I think Putin’s primary strategy is about getting concessions from the US and the West. The Ukraine crisis is what has brought the Americans to the table, so the invasion threat needs to be quite credible.”

Like most analysts, Hess believes that, if an invasion were to occur, it would probably remain in eastern Ukraine, not the western regions that border the EU. Bender agrees, saying: “From Putin's point of view, it is such a good opportunity... with the West being so disunited. This is not about Nato, which, like Germany, is quite weak in Europe. Russia is the biggest military force in that region.” Domestically, Putin has not achieved much for Russia's economy outside of big cities such as Moscow and St Petersburg, so an invasion would be a big win for his narrative of reclaiming the country's sphere of influence, its global status, as well as temporarily raising the price of oil to (probably) more than $100 per barrel, adds Bender.

Back on the ground in Ukraine, an eastern venture would consolidate the territories already under Putin’s control, replacing proxy forces with actual Russian troops in Donbas, for example. He may accompany this by taking the industrial coastal city of Mariupol, which lies very close to Russia, not far from Donetsk, which was seized by pro-Russian rebels in 2014 and turned into the de facto capital of the Donetsk People's Republic. Mariupol is home to two of the largest steel factories in Ukraine, both of which are owned by the oligarch Rinat Akhmetov, one of Ukraine’s richest businessmen.

According to Hess, next in Putin’s sights could be Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, since it too is very close to the Russian border. In 2014, the Russian rebels attempted (and failed) to launch a people's republic movement there too. It is also plausible that Russians will seek to take the whole of Ukraine’s south-east, bridging their southerly coastal outpost of Crimea with the separatist areas in the east.

An incursion like this would take out major industrial cities such as Zaporizhzhia, Dnipro and Kryvyi Rih, which are home to huge steel industries. Invading them would have significant effects on energy dynamics throughout Ukraine because of the hydropower dams that are there, as well as for the power and water future of Crimea under Russian control.

More importantly, the capture of south-east Ukraine would cut Kyiv and the western region off from the Black Sea, home to most of Ukraine’s key ports and trade nodes (especially for foodstuffs and military equipment).

“There is a small possibility that Russia may take Odessa on the west coast," says Hess. "I don’t think they will go as far as Kyiv. If they did go west, it would probably be Russian destruction of Ukrainian air bases.”

Another black swan event could be Ukraine’s partition, should Putin take most of the east. “In this scenario, eastern Ukraine would become a pariah to international investment and trade, while the western part would very quickly join the EU and see a real investment boom," says Hess. "Already, western Ukraine is culturally and economically aligned with western Europe.”

This is why the vast majority of foreign investment to Ukraine has gone to the western regions, with the biggest investors being German automotive companies. Ukraine is an important part of the EU’s car component supply chain, especially for the programming of satellite navigation systems and other digital devices used in vehicles.

Meanwhile, in Odessa, large US companies such as Cargill have invested in the port, alongside exporters like Singapore’s Delta Wilmar and Poland’s Kernel. Across Kyiv and Lviv, over a hundred thousand are employed in business process outsourcing for the world's big tech companies, such as Facebook, explains Bender.

Foreign investors in Ukraine are preparing for an invasion

The threat of Russian invasion has already disrupted specific industries in Ukraine, especially tourism.

“The situation happening at the moment has slowed the rise of the inbound and outbound travel flow, as European airlines such as Lufthansa, Austrian Airlines and Swissair have cancelled flights with overnight stopovers in Boryspil airport [in Kyiv],” says Shapovalova.

Based on Investment Monitor’s discussions with several political risk consultancies, it would seem that a lot of foreign companies, both within the tourism sector and elsewhere, are thinking about the potential impacts of invasion and drawing up contingency plans.

“If you look at Ukrainian and Russian credit default swaps, the weakening of the Russian ruble, Ukrainian debts, and international businesses in Ukraine, there are clear indications that people are significantly worried,” says Hess.

Myroshnychenko has fielded requests from clients on how the crisis may develop and how to respond to it. He advises that the strategy depends on the sector they are in. “We have many companies in the IT and tech industries in Ukraine," he says. "For them it is more straightforward, as they can move employees temporarily to countries such as Poland and continue operations, as their clients are mainly based in the UK and the US.”

The situation is not as simple for manufacturers, food processing companies and agribusinesses with major physical operations in Ukraine. “Those trading grain and other agricultural produce are very concerned about what the Russian Black Sea fleet can do, as they can block major ports such as Odessa," says Myroshnychenko. "Companies would not be able to get their products out of the country, which would be a major disruption to our economy.”

Myroshnychenko believes that, even if no invasion occurs, it will be difficult to rebuild a positive image of Ukraine as an attractive investment destination. “We have a belligerent neighbour that is not going to stop being a threat while Putin is in power," he says. "Even if there is no conflict now, we will need another six to seven months for the storm to calm down and for international investors to be reassured about our macroeconomic situation.”

On the other hand, Bender is confident about the resilience of the Ukrainian economy, insofar as, even after the 2014 conflict, foreign investors still found the country an attractive destination. For example, Cargill, whose Donetsk plant was seized by rebels, still went ahead an invested in the Odessa port. Several other foreign companies also shifted operations away from Donetsk to safer parts of Ukraine, rather than abandoning the country.

Just how far Putin will go (quite literally) with Ukraine is anyone’s guess over the coming weeks. It seems most reasonable for investors to expect low level incursions across the south-east, while also not ruling out black swan events such as a fully partitioned Ukraine, à la Cold War Germany. However, the latter would require from Putin remarkable recklessness in the shape of barefaced disregard for economic sanctions, such as the cancellation of Russia’s all-important Nord Stream gas pipeline to Germany.

Whatever happens, Putin has already succeeded in bringing global players to the negotiating table and raising Russia’s global profile. Once again, the Kremlin seems to operate on the principle of ‘all press is good press’ – just not for the world of international business and foreign investment. In this regard, Putin knows very well that Ukraine will pay the highest price.

LINK: https://www.investmentmonitor.ai/analysis/ukraine-russia-business-impact-investment

Sebastian Shehadi is political editor and senior editor at Investment Monitor and a contributing writer for the New Statesman. He joined from the Financial Times, where he was an editor at fDi Magazine. He takes special interest in tourism, tier-two cities, green energy, real estate and emerging markets, and has written for the FT, the BBC, Sifted and Middle East Eye. Prior to his career in journalism, Sebastian served as a political risk analyst at Citibank.

Jon Whiteaker is a senior editor at Investment Monitor focusing on FDI in the energy sector. He is also Middle East and Africa editor. He joined from Euromoney Institutional Investor. He has been a business and finance journalist for more than a decade, five of which he spent as the editor of IJGlobal – a leading news and data title covering energy and infrastructure finance. Jon has reported on transactions and investment trends across all continents and is an experienced leader and participant in industry events.