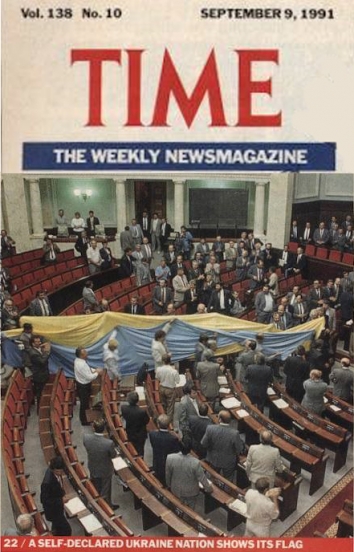

Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

Time to Come Together

COSA, Kyiv, Ukraine,

COSA, Kyiv, Ukraine,

Dec 11, Fri, 2020

Peter Kopka, Principal Expert and Strategic Adviser at COSA

Peter Kopka, Principal Expert and Strategic Adviser at COSA

Peter was the founder of the Analytical Division of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine. In 2003 he was the acting head of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine. Peter retired in 2004 in the rank of Major-General and until 2010 worked as rst deputy director of the Institute of problems of national security of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine. Petro joined COSA in 2014 and since then he has provided expertise in regard to the methodology of research, as well as contributed into COSA’s enhanced political, economic and security risk analysis in the framework of widescale risk assessment, research and monitoring projects.

21st Century Plague The pandemic has made additional, unexpectedly massive changes to the progression of international events. Firstly, the pandemic factor took on a life of its own as soon as it emerged, while also becoming a useful instrument of inuence various global actors did not miss the opportunity to employ in order to achieve their own political and economic purposes. Some of them use it as an instrument of intimidation to put (broadly speaking) their house in order, while others see the pandemic as a temporary inconvenience that will soon go away like the u and thus does not warrant special attention.

As the events unfolded, these two factions were forced to come closer together. If initially the threat was underestimated, completely ignored, or met with a panic, in time a consensus has emerged, making most countries realise COVID-19 is a grave, long-term danger (at least a latent one).

Nevertheless, instead of joining efforts to stem the pestilent tide by nding an effective cure, the leading global actors chose self-isolation. This national egoism of the world’s democracies has become one of the key factors exacerbating the effects of the coronavirus. Instead of working together to develop a vaccine, the global actors started a race to conquer the global market. Competition is obviously a ne thing, but a vaccine is not a mere commodity. The lives of millions, if not billions, of people depend on its quality.

Its development most certainly should not be rushed, least of all when the nature of the disease is not fully understood. Unfortunately, the race has already begun. As it has become customary in such situations, Russia did not miss the opportunity to take advantage of the confusion. Faced with an alarming decrease in prices for crude hydrocarbons, the Kremlin has found a way to replace them as a key source of income, with the Russian vaccine projected to generate USD 100 billion a year.

Like the Russian president said, “it’s good business as well.” Political and nancial expediency has overruled sound medical judgement. The current situation with the Russian vaccine only goes to show that the old adage about haste making waste is still true. Instead of earning the country billions, Sputnik-5 merely serves as a yet another example of the wrong way to solve complex system tasks.

In spite of everything, the difcult work to develop a vaccine continues. However, one should bear in mind that vaccination would only build herd immunity, whereas our main goal should be nding a cure for coronavirus in addition to preventative measures.

Developing such a cure is another matter altogether, a problem that will take years to solve. Thus, it is safe to say that the effects of the pandemic are long-term and will remain detrimental to the global society for many years to come. Economy in Times of the Pandemic The rst steps taken to slow down the spread of the virus (quarantine of various levels of severity up to lockdowns in many places) could not help but undermine the global economy and world economic cooperation. In turn, a slowdown in business activity affected the international energy market and caused the dichotomy in oil prices.

At the same time, the quarantine measures combined with government support helped fend off the initial attack of COVID-19 more or less successfully. In August, unemployment levels dropped and the situation on the housing market improved in the United States, the Chinese economy showed signs of recovery, and Germany’s production industry started growing again. This summer’s positive dynamics has even made some analysts condent enough to project a global business recovery in the third and fourth quarter of 2020. However, this autumn has shown that the very real threat of a second wave of COVID-19 cases necessitates a reassessment of the recent overly optimistic projections.

Current prognoses estimate the probability of a second global lockdown as moderate but increasing. Even if there is no lockdown, the global economy will probably continue to struggle and face mass unemployment. Thus, economic recovery efforts are now limited to two options, either the economy is boosted while death rates increase or a lockdown is announced to save the population at the expense of the economy. Sweden and Denmark are perfect examples illustrating this point.

In February–May 2020, Sweden refused to implement lockdown measures, and now its GDP is expected to decrease by 7%, while other economies have shrunk by 30%. The WHO cites Sweden’s example as an effective strategy to ght the coronavirus. However, the coronavirus fatality rate in Sweden is several times higher than in neighbouring Denmark. According to John Hopkins University, of the 84,900 COVID-19

This dilemma will remain relevant for a long time. The Unstable Shape of Things to Come Thus, we may observe that the global community is currently trying to nd its way between two opposites, utilitarianism versus humanism. Countries that choose humanism protect their citizens but risk hurting their economies beyond repair. Meanwhile, those who choose utilitarianism preserve their economies at the risk of facing grave demographic problems.

This juxtaposition is expected to disappear when a vaccine is developed, but a vaccine will not necessarily mean humanity’s victory over coronavirus. It will probably have a shortterm psychological effect that will not be strong enough to reboot the global economy and restore our former way of life. Much more effort, beyond mere vaccination, will be needed to achieve this. Firstly, it should be understood that the world cannot go back to the way it was, at least not entirely. This conclusion stems from the consistent patterns in which systems develop. The pre-coronavirus world cannot be reproduced exactly. At best, it will be something similar, but not identical, and only if humanity manages to join efforts and achieve synergy.

It will not be possible if humanity continues to run along the tracks of the old bipolar world that was rooted in antagonism. Secondly, regardless of differing opinions, our world is still run by charismatic leaders. The global society needs a leader, without whom it cannot even develop a roadmap for the short term. The United States’ voluntary seclusion from international politics has resulted in a drastic weakening of international institutions and multilateral treaties, including those in international defence, while increasing national egoism, which has plunged the global society in chaos. As the role of nation states in international affairs grew, their political and administrative elites were increasingly (and legally) penetrated by unabashed populists who are unable to solve any real problems, internal or international.

This era in the global history seems to be gradually receding into the past. The recent presidential election in the USA may be taken as a sign that one can look to the future with cautious optimism in this regard.

Others try to compensate for security deciencies by means of internal mobilisation and strengthening of the power vertical. It is no coincidence that some countries are now moving away from pluralistic democracy and trying to create authoritarian or totalitarian surrogates. Interestingly, they are doing it openly, at the legislative level. In this respect, a new trend has emerged. Before, it was the countries with no real inuence over global processes that replaced democracy with something else.

Now, such transgressions are committed by G20 member states. Therefore, in the short and medium term, we shall see how liberal ideas and democracy fare in the post-coronavirus world. Will our freedoms return? Or will the world continue to descend into authoritarianism? In Lieu of a Conclusion The COVID-19 pandemic has been humanity’s rst real global challenge since the collapse of the bipolar world order.

To overcome it, our collective efforts must achieve synergy. Moreover, the pandemic has offered the global society a real chance to rid itself of the outdated paradigm of global confrontation. Unfortunately, humanity has so far been acting in the same old way, refusing to take this unique opportunity, even though it has already become clear that humanity’s survival depends on all countries joining efforts to tackle the problem. The time to cast away stones has passed. It is now time to gather the stones together.