Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

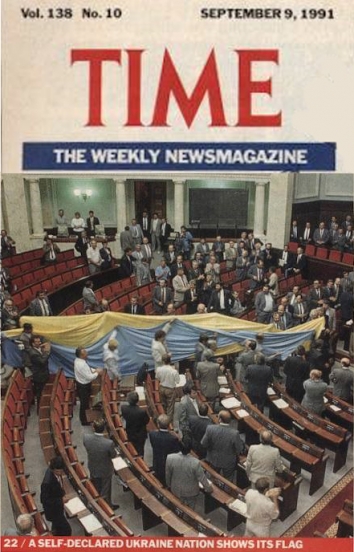

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

UKRAINIAN AMERICANS STRUGGLE TO GET FLEEING RELATIVES INTO UNITED STATES

By Mark Fisher, Maria Sacchetti and Mark Shavin

By Mark Fisher, Maria Sacchetti and Mark Shavin

Washington Post, Wash, D.C., Sat, Mar 19, 2022

Ukrainian refugees pass through a checkpoint to enter the United States through Mexico. (Jorge Duenes/Reuters)

Every morning and every night, from her home in Falls Church, Va., Nadiia Khomaziuk messages her sister Lidiia in her hideaway in western Ukraine.

Is Lidiia still okay? How about her kids, who are 7 and 11? Every day, Khomaziuk scours the Internet, calls U.S. government offices and connects with lawyers and other Ukrainian Americans, in search of a path to bring her family to safety in the United States.

To get to there, Khomaziuk’s family and other Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion would need a visa, but the earliest appointment Khomaziuk could get for an interview for her sister at the U.S. Embassy in Warsaw is in September.

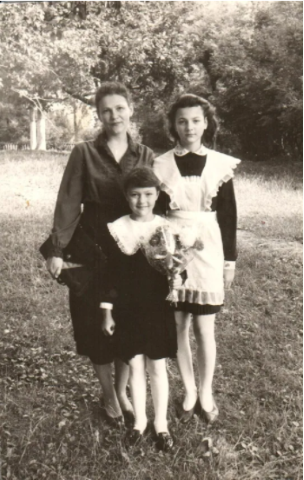

Nadiia Khomaziuk, center, poses with her sister

and mother in Zdolbuniv, Ukraine, in 1994. (Family Photo)

Lidiia, who asked that her last name not be published because of security concerns, isn’t ready to leave Ukraine. She wants to fight “till the last breath,” Khomaziuk said, though “the kids’ bags are packed, so they can jump in the car the minute they need to. But then I don’t know if I can get them here. Waiting six months for an interview just isn’t right.”

More than 3 million Ukrainians have fled their ravaged country, and the great majority of them are in the border states of Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Moldova and Hungary, according to the United Nations.

As Russian missiles obliterate more cities, refugees crowded into family basements and church social halls across Eastern Europe confront a painful choice to hold out where they are or try to be resettled as refugees, possibly in faraway countries.

Over 5,000 miles away, the reality is setting in for Ukrainian Americans eager to bring their relatives to safety that despite government pledges of solidarity, getting into the United States is a lengthy and cumbersome process that remains largely unchanged from before the war, according to those trying to bring relatives into the country and advocates who are helping them.

Still, a trickle of Ukrainians are making it to the United States to reunite with relatives, for medical care, or on tourist visas, even as many of them remain torn between craving safety for their families and feeling drawn to the mission of defeating the Russians.

Khomaziuk, who works at the U.S.-Ukraine Business Council, understands that to her sister Lidiia, a 40-year-old music teacher, this is the time to keep on baking cookies for soldiers and doing whatever she can to help other Ukrainians who’ve had to flee from burning homes.

“But I want to be able to bring my nephew and niece here,” Khomaziuk said. “I’m ready to go fly and pick them up at the border.” She remains, however, stuck in waiting mode, dependent on a U.S. visa system that is hopelessly backed up. “They really need to fly more customs people into Warsaw to speed up the process,” said Khomaziuk, 36.

This picture from Nadiia Khomaziuk shows her with her sister

and family near Zdolbuniv last summer. (Ania Mischuk)

Some lawmakers and advocacy groups are urging the Biden administration to expedite the arrival of Ukrainians. But officials say the refugee system is not built for speed, as the U.S. vetting process often takes years.

President Biden has said he would accept up to 125,000 refugees from around the world this fiscal year, but barely 6,500 arrived between October and February, federal records show. More than 20 million refugees are under the U.N. refugee agency’s mandate, from troubled nations such as Syria, the Central African Republic and Venezuela. That number does not include more than 70,000 Afghan military interpreters and other allies the U.S. government evacuated from Afghanistan last year as the Taliban took over that country.

In the case of Ukraine, a State Department official said in a written statement, most refugees want to stay in Europe “in the hope they can return home soon” and if there are Ukrainians “for whom resettlement in the United States is a better option,” U.S. officials will work with U.N. and European officials to consider them, “bearing in mind that resettlement to the United States is not a quick process.”

One backdoor entrance to the United States that a few Ukrainians have been using is to fly to the Mexican border and beg to be allowed in. Homeland Security officials said a trickle of Ukrainians, with a daily volume in the “double digits,” have been taking advantage of the fact that they don’t need a visa to enter Mexico, so they fly to a Mexican border city, usually Tijuana, then head to the U.S. port of entry at San Ysidro, south of San Diego.

Ukrainians walk on the Mexican side of the border after trying to enter the United States.

(Guillermo Arias/AFP/Getty Images)

U.S. government data show that at least 1,300 Ukrainians were taken into custody along the Mexico border between Oct. 1 and Feb. 28. Homeland Security officials said they are allowing some Ukrainians to enter, exempting them from the public health order that U.S. authorities have used during the pandemic to turn back most asylum seekers.

“We are responding to the humanitarian crisis caused by the tragic events in Ukraine by granting humanitarian parole, on a case-by-case and temporary basis, to Ukrainians who have fled the crisis,” Homeland Security spokesman Eduardo Maia Silva told The Post.

The Biden administration is sending hundreds of millions of dollars in security and humanitarian aid, including personal hygiene kits, blankets, winter gear and food, to Ukraine and supporting European nations and nonprofits that are hosting refugees. Last week, about 75,000 Ukrainians already in the United States on student, tourist or business visas won temporary humanitarian protection from deportation, a status that will let them apply for work permits.

Lubov Stelmakh is about to board a charter bus leaving Kyiv

for Moldova. Her daughter, Zhenia, and son-in-law, Alan,

live in a suburb north of Atlanta. (Family Photo)

That’s not good enough for Alan and Zhenia Kaplan, an Atlanta-area couple who are desperate to get Zhenia’s 81-year-old mother, Lubov Stelmakh, to safety in Peachtree Corners, Ga., where Alan is a real estate broker and Zhenia is a homemaker.

As Kyiv came under attack, Stelmakh, who had never been outside Ukraine and was reluctant to leave, boarded a bus sponsored by an Orthodox synagogue and headed for neighboring Moldova, a long journey into a new world.

Stelmakh got on the wrong bus, Alan said, but he was grateful it took her to a synagogue in the Moldovan capital of Chisinau instead of to a large refugee center. “She is in a strange country,” Alan said, “a very hospitable, thank God, country” but “we can’t even get her here with the immigration and visa processes that we have.”

“This is a literal exodus,” said Zhenia, sitting in her den as the news on the television showed Ukrainian buildings reduced to rubble. “In every generation, there is evil. In this generation, it’s Putin.”

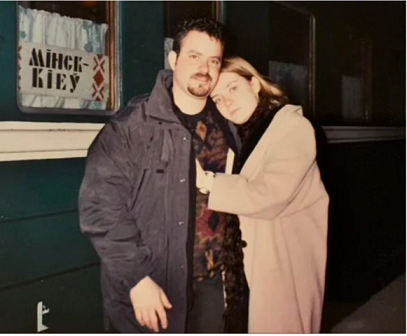

Alan and Zhenia Kaplan met on a Passover mission trip to Minsk in 1999.

They now live near Atlanta. (Family Photo)

Zhenia, 44, and Alan, 57, met on a Passover mission trip to Minsk, Belarus, in 1999. He had traveled from Atlanta and she from Kyiv to bring the biblical story of Exodus and the traditional Seder meal to communities that had lost touch with their Jewish roots under communist rule.

Now, as another exodus traps Zhenia’s relatives in a war zone, the Kaplans find themselves stuck in red tape, unable to help their family, even as the couple promises to sponsor and support them.

Zhenia’s sister, Irina, 51, made it from Kyiv to the relative safety of western Ukraine on the third day of the war, riding for 17 hours on a packed train with her 14-year-old daughter, Veronika.

With her sister in western Ukraine and her mother sleeping in a synagogue classroom in Moldova, Zhenia has been working around-the-clock to get them somewhere safe. The United States appears not to be an option.

“There is no procedure for them to even apply for a visa,” she said. “They can’t apply in Ukraine. So they have to apply in another country like Poland or Moldova.” That seems logistically impossible, but the Kaplans aren’t giving up yet. They’re now considering traveling to Moldova to press their effort to get Stelmakh to the United States or Israel.

Zhenia Kaplan, left, seen with her sister, right, and parents in the back row

Zhenia Kaplan, left, seen with her sister, right, and parents in the back row

at their family home in Kyiv. (Family Photo)

Olga Hull, 40, shares their frustration. She wants to bring her younger sister, Anna, and Anna’s two young children to the United States to live with her, at least temporarily. They fled Ukraine for Poland, then the Czech Republic. Anna, who asked that her last name not be published because of security concerns, spent $500 to travel to Munich for a day to apply for a tourist visa at the U.S. Consulate.

But Anna’s costly gamble ended in frustration, as she was unable to persuade consular officials that she would stay in the United States temporarily, even after she explained that she had a job, husband, parents and a 95-year-old grandfather counting on her return to Ukraine, Hull said.

“For her, it’s kind of like an insult,” Hull said, quoting her sister’s reaction to the worry from officials that Anna might end up overstaying her tourist visa. “How can I not come back? I love my husband. My husband is there,” Anna told her.

Olga Hull, left, with her younger sister, Anna, at their family home

near Rivne in Ukraine last summer. (Family Photo)

Anna and her children are now in Prague, where Hull, who lives in Dover, N.H., said she will help pay for the family’s temporary housing. Hull called on Biden to “simplify the visa, at least for the siblings, cousins, children, parents. Do it faster, like other countries.”

For some Ukrainian Americans, the contrast between their inability to get their relatives into the country and the heartwarming welcome that many people who fled Afghanistan received from Americans last summer is jarring.

“It’s very unfair that Ukrainians don’t get a chance to reunite with their families,” said Iryna Valles, 36, who came to the United States a decade ago and lives in Alpharetta, Ga. “Yet a few months ago, we had all of these planes coming from Afghanistan.”

Valles, a U.S. citizen, said the United States should let families like hers who can provide for their relatives bring them here. Her sister Nataliia, 33, and her 12-year-old son Kirill fled their hometown of Chernihiv, which Valles said has been “pretty much leveled.”

Now in Warsaw, they have little hope of making it to the United States since they’ve been unable to get an interview to apply for a visa. “They won’t give you a date,” Valles said.

Iryna Valles, left, poses with her sister Nataliia, who fled to Poland

from Chernihiv, Ukraine, with her son. (Iryna Valles)

Ukrainians have been coming to the United States as refugees for decades, most recently around the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, when Ukrainians overwhelmingly voted for independence. Now, while many want to join relatives in the United States, many others want to stay in Europe, hoping to help in the fight against Russia and then return home as quickly as possible.

“They don’t want to leave,” said Nataliya Russo, 59, who came to the United States in 1999 as a former high school math teacher and folk dancer. She arrived with a 13-year-old daughter, $500 and a cat. Now a medical aesthetician in Birmingham, Ala., Russo is concerned about her 52-year-old brother in Kryvyi Rih, Ukraine, and his wife and two daughters.

Despite harrowing stories of bombs raining down on her brother’s neighborhood, Russo is not pushing him to get out. “They are patriots,” she said. “They want to wait it out and rebuild.”

Americans like Russo are eager to help. When two Harvard students, Marco Burstein and Avi Schiffmann, launched an online service designed to match fleeing Ukrainians with hosts around the world, hundreds of Americans joined thousands of Europeans in volunteering extra bedrooms and basements to house refugees.

“But the great majority are in Europe,” Burstein said. “It’s all a question of where the demand is, and that’s in Eastern Europe, which is where the Ukrainians want to be. In terms of the United States, it’s pretty theoretical.”

The United States “isn’t ready for them and they don’t really want to come here yet because they’re still intending to go back home,” said Tamara Woroby, parish council president at St. Andrew Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral in Silver Spring, Md., and an economist at Towson University who studies immigration policy. “We don’t have a process for them. Unless they already had visas, there isn’t a way for them to get here.”

But some Ukrainians are getting visas and making it to the United States. Before the bombs fell and tanks rolled in, Roman Vashchuk was far from his home in Irpin, near Kyiv, on an American Christian mission tour. He was bringing his Ukrainian Christmas songs to church audiences in the Midwest and the Pacific Northwest. He was in Seattle when he contracted the coronavirus and ended up hospitalized with a mild stroke. Doctors said that because of a blood clot, he could not travel for several months.

Vashchuk’s wife, Roza, and their three young children were stuck in Irpin. When Russia invaded, the singer and his wife scrambled to reunite the family. One night in late February, as Roza and the children scurried into an underground shelter after hearing Russian planes and helicopters overhead, her brother called. “Get your things,” he ordered. “We are leaving now.” Neighbors tried to hold her back. “You can’t go out now,” they said. “There’s bombing.”

But Roza’s brother insisted this was their chance. With one bag of essentials, the family jumped into the car and raced westward toward Poland. What was normally a three-hour drive to Rivne in western Ukraine took 13 hours. After hiding out there for over a week, Roza, her three kids, and a friend with her two boys drove another 17 hours on jammed roads into Poland.

Roman Vashchuk and his wife Roza with their Ukrainian passports

after reuniting with family near Seattle. (Stuart Isett)

Determined to get to Roman in Seattle, Roza had the advantage of U.S. tourist visas for herself and her two older children, ages 10 and 7, that were valid for 10 years following their 2019 visit to the United States. But her one major obstacle was that their daughter Solimia, who is 20 months old, hadn’t been born yet when the Vashchuks made that last trip, so she had no visa.

Back in Seattle, Roman, 44, now out of the hospital, was doing all he could to bring attention to his country’s plight and his family’s need. He sang the Ukrainian anthem to 17,000 fans at a Seattle Kraken hockey game, went on television to plead for U.S. support for Ukraine, and spread the word about his family’s quest to reunite.

Roza made her way to Krakow, where the next appointments for visa interviews at the U.S. Consulate were in August. Roza insisted on speaking to a consular official and explained that Solimia was still a fetus on the family’s last U.S. visit. Could the United States issue one more visa to allow the family to reunite?

Her plea worked. She bought plane tickets, and on Monday, Roza and the children completed their odyssey, flying from Krakow, Poland, to Amsterdam to Seattle, where the two older kids, Milana, 10, and Nathan, 7, spotted their father, who held a bouquet of two dozen red roses for Roza. The children shouted, “Papa!” and ran to Roman, leaping into his arms. “It was a miracle,” Roza said. “God made a miracle.”

Roman and Roza Vashchuk enjoy breakfast with their children

at the home of a pastor in Washington state. (Stuart Isett)

They are staying in the home of the pastor of Life of Victory Church in Renton, Wash., a fellow Ukrainian who came to the United States 20 years ago. How long they’ll be there, they do not know. Their neighbors in Ukraine tell them that “our city is destroyed,” Roza said.

“We left everything. Our albums with pictures. Everything. It makes us so sad. We don’t know if we’ll ever have the opportunity to come back,” Roza said. For now, they have only thanks, for their safety and for being together. Roman plans to sing songs of gratitude at a concert in Seattle on April 3.

Even a visa does not guarantee such a happy ending for some Ukrainian families. Oksana Palchevska, a postdoctoral fellow in microbiology who came to Birmingham in 2020 to join a University of Alabama research project on the coronavirus, has been working here while her husband and 12-year-old daughter Sofiia remained in Ukraine.

“I was stupid not to take my family with me, I see now,” Palchevska said. But at the time, few people foresaw this kind of conflagration. Last December, her husband Sergii and Sofiia got J-2 visas, granted to immediate relatives of a nonimmigrant who is working in the United States.

But earlier this year, Sergii, a scientist who had been working at an institute in Poland, made one last trip back home to Kyiv to say goodbye to his family before heading to the United States. He stayed too long, Palchevska said, and now is stuck in Ukraine because the country is requiring men to stay to fight the Russians.

Sofiia had remained in Warsaw with Palchevska’s sister and parents. Luckily, the sister holds a U.S. tourist visa, so Palchevska hopes her sister will be allowed to bring Sofiia to Alabama this weekend. Palchevska, 36, has sent letters asking U.S. officials to let her daughter into the country without a parent accompanying her, but she won’t know whether it will all work out until the day of the flight.

Palchevska is allowing herself a bit of optimism that Ukraine will hold off the Russians, Sofiia will be with her soon and they will edge into an American life. Palchevska got a driver’s license and is looking to get her first car so she can take her daughter to her American school.

“I feel a little guilty that I should be in my country to help,” Palchevska said. “I don’t fit into this country yet. Mostly, I work. But there are so many more opportunities here.”

Protesters carry a Ukrainian flag in the District of Columbia last month.

(Leigh Vogel for The Washington Post)

Fisher and Sacchetti reported from Washington and Shavin reported from Atlanta. Nick Miroff in Washington contributed to this report.

NOTE: Marc Fisher, a senior editor, writes about most anything. He has been The Washington Post’s enterprise editor, local columnist and Berlin bureau chief, and he has covered politics, education, pop culture and much else in three decades on the Metro, Style, National and Foreign desks.

Maria Sacchetti covers immigration for the Washington Post, including U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the court system. She previously reported for the Boston Globe, where her work led to the release of several immigrants from jail. She lived for several years in Latin America and is fluent in Spanish.

LINK: Ukrainian Americans struggle to get fleeing relatives into United States