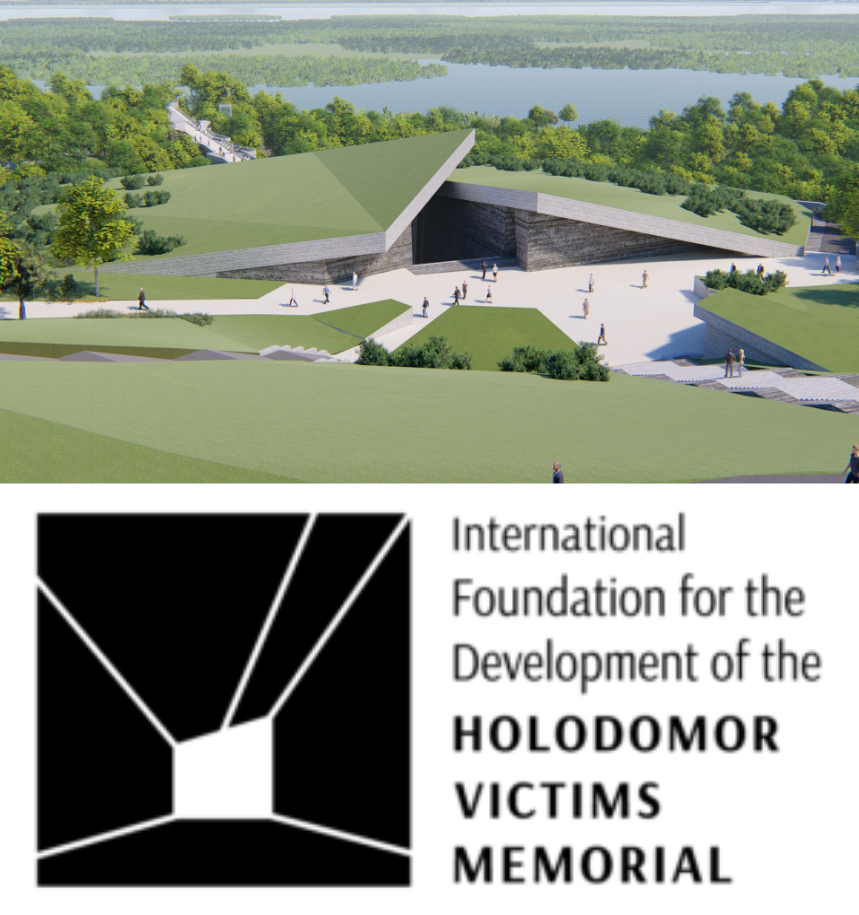

Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

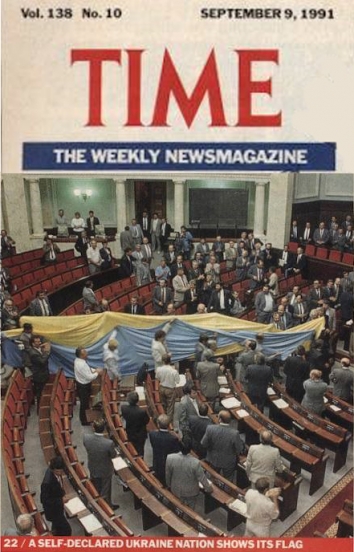

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

UKRAINIAN AMERICANS STRUGGLE TO GET FLEEING RELATIVES INTO UNITED STATES -- Part 2

By Mark Fisher, Maria Sacchetti and Mark Shavin

By Mark Fisher, Maria Sacchetti and Mark Shavin

Washington Post, Wash, D.C., Sat, Mar 19, 2022

Anna and her children are now in Prague, where Hull, who lives in Dover, N.H., said she will help pay for the family’s temporary housing. Hull called on Biden to “simplify the visa, at least for the siblings, cousins, children, parents. Do it faster, like other countries.”

For some Ukrainian Americans, the contrast between their inability to get their relatives into the country and the heartwarming welcome that many people who fled Afghanistan received from Americans last summer is jarring.

“It’s very unfair that Ukrainians don’t get a chance to reunite with their families,” said Iryna Valles, 36, who came to the United States a decade ago and lives in Alpharetta, Ga. “Yet a few months ago, we had all of these planes coming from Afghanistan.”

Valles, a U.S. citizen, said the United States should let families like hers who can provide for their relatives bring them here. Her sister Nataliia, 33, and her 12-year-old son Kirill fled their hometown of Chernihiv, which Valles said has been “pretty much leveled.”

Now in Warsaw, they have little hope of making it to the United States since they’ve been unable to get an interview to apply for a visa. “They won’t give you a date,” Valles said.

Iryna Valles, left, poses with her sister Nataliia, who fled to Poland

from Chernihiv, Ukraine, with her son. (Iryna Valles)

Ukrainians have been coming to the United States as refugees for decades, most recently around the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, when Ukrainians overwhelmingly voted for independence. Now, while many want to join relatives in the United States, many others want to stay in Europe, hoping to help in the fight against Russia and then return home as quickly as possible.

“They don’t want to leave,” said Nataliya Russo, 59, who came to the United States in 1999 as a former high school math teacher and folk dancer. She arrived with a 13-year-old daughter, $500 and a cat. Now a medical aesthetician in Birmingham, Ala., Russo is concerned about her 52-year-old brother in Kryvyi Rih, Ukraine, and his wife and two daughters.

Despite harrowing stories of bombs raining down on her brother’s neighborhood, Russo is not pushing him to get out. “They are patriots,” she said. “They want to wait it out and rebuild.”

Americans like Russo are eager to help. When two Harvard students, Marco Burstein and Avi Schiffmann, launched an online service designed to match fleeing Ukrainians with hosts around the world, hundreds of Americans joined thousands of Europeans in volunteering extra bedrooms and basements to house refugees.

“But the great majority are in Europe,” Burstein said. “It’s all a question of where the demand is, and that’s in Eastern Europe, which is where the Ukrainians want to be. In terms of the United States, it’s pretty theoretical.”

The United States “isn’t ready for them and they don’t really want to come here yet because they’re still intending to go back home,” said Tamara Woroby, parish council president at St. Andrew Ukrainian Orthodox Cathedral in Silver Spring, Md., and an economist at Towson University who studies immigration policy. “We don’t have a process for them. Unless they already had visas, there isn’t a way for them to get here.”

But some Ukrainians are getting visas and making it to the United States. Before the bombs fell and tanks rolled in, Roman Vashchuk was far from his home in Irpin, near Kyiv, on an American Christian mission tour. He was bringing his Ukrainian Christmas songs to church audiences in the Midwest and the Pacific Northwest. He was in Seattle when he contracted the coronavirus and ended up hospitalized with a mild stroke. Doctors said that because of a blood clot, he could not travel for several months.

Vashchuk’s wife, Roza, and their three young children were stuck in Irpin. When Russia invaded, the singer and his wife scrambled to reunite the family. One night in late February, as Roza and the children scurried into an underground shelter after hearing Russian planes and helicopters overhead, her brother called. “Get your things,” he ordered. “We are leaving now.” Neighbors tried to hold her back. “You can’t go out now,” they said. “There’s bombing.”

But Roza’s brother insisted this was their chance. With one bag of essentials, the family jumped into the car and raced westward toward Poland. What was normally a three-hour drive to Rivne in western Ukraine took 13 hours. After hiding out there for over a week, Roza, her three kids, and a friend with her two boys drove another 17 hours on jammed roads into Poland.

Roman Vashchuk and his wife Roza with their Ukrainian passports

after reuniting with family near Seattle. (Stuart Isett)

Determined to get to Roman in Seattle, Roza had the advantage of U.S. tourist visas for herself and her two older children, ages 10 and 7, that were valid for 10 years following their 2019 visit to the United States. But her one major obstacle was that their daughter Solimia, who is 20 months old, hadn’t been born yet when the Vashchuks made that last trip, so she had no visa.

Back in Seattle, Roman, 44, now out of the hospital, was doing all he could to bring attention to his country’s plight and his family’s need. He sang the Ukrainian anthem to 17,000 fans at a Seattle Kraken hockey game, went on television to plead for U.S. support for Ukraine, and spread the word about his family’s quest to reunite.

Roza made her way to Krakow, where the next appointments for visa interviews at the U.S. Consulate were in August. Roza insisted on speaking to a consular official and explained that Solimia was still a fetus on the family’s last U.S. visit. Could the United States issue one more visa to allow the family to reunite?

Her plea worked. She bought plane tickets, and on Monday, Roza and the children completed their odyssey, flying from Krakow, Poland, to Amsterdam to Seattle, where the two older kids, Milana, 10, and Nathan, 7, spotted their father, who held a bouquet of two dozen red roses for Roza. The children shouted, “Papa!” and ran to Roman, leaping into his arms. “It was a miracle,” Roza said. “God made a miracle.”

Roman and Roza Vashchuk enjoy breakfast with their children

at the home of a pastor in Washington state. (Stuart Isett)