Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

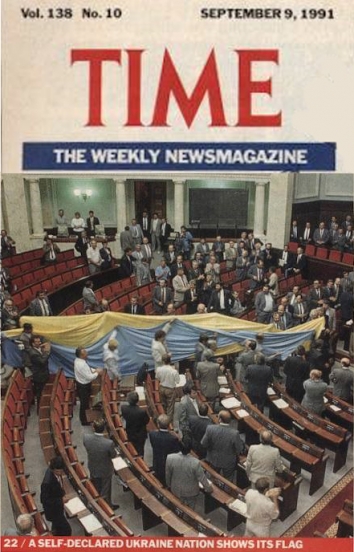

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC) charges ahead

in its 26th year

.jpg) U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC) charges ahead in its 26th year by Askold Krushelnycky for Kyiv Post

U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC) charges ahead in its 26th year by Askold Krushelnycky for Kyiv Post

July 09, Fri, 2021

.jpg) WASHINGTON — The U.S.-Ukraine Business Council, an organization that helps forge deeper ties between Ukraine and arguably the nation’s most important ally, America, is celebrating its 26th year.

WASHINGTON — The U.S.-Ukraine Business Council, an organization that helps forge deeper ties between Ukraine and arguably the nation’s most important ally, America, is celebrating its 26th year.

From today’s membership of 220 businesses, including the Kyiv Post, the council grew from humble beginnings. It started as an ad hoc group of seven companies in 1995 when former President Leonid Kuchma asked to meet with American businesspeople on a visit to Washington, D.C.

By the time Morgan Williams started working with the group 16 years ago, the organization had only eight members. Williams, who first came to Ukraine in 1993, took over the council as acting head in 2007. He and the organization never looked back. Williams has been its leader ever since, serving with dual titles as president and CEO for more than 13 years.

Williams brought with him extensive business and political experience, including work for Congress. Steadily, with the help of others, the USUBC grew to its size today. It keeps an office in Kyiv and Washington, D.C.

Williams credits a prominent group of supporters as instrumental in building the USUBC, including investor Michael Bleyzer. Van Yeutter of Cargill, Irina Palashivili of the RULG-Ukrainian Legal Group, USUBC legal counsel Jack Heller, Eric Luhmann of Amsted Rail Company, and Michael Kirst of EuroAtlantic Partners.

Besides advocating for better economic ties, the USUBC has also incorporated cultural initiatives and other projects to raise awareness about Ukraine in America.

How it happened

Williams was working for SigmaBleyzer as government relations director of the Washington, D.C., office when he agreed to help grow USUBC. SigmaBlezyer, a private equity firm with major investments in Ukraine, is co-founded by Bleyzer, a Ukrainian native who moved to America. Bleyzer serves as its president and CEO.

The U.S.-Ukraine Business Council has an executive committee of 15 members and every member has a seat on the board of directors. The members boast a formidable network of contacts in Washington among politicians, federal agencies, and international financial institutions to troubleshoot and solve problems of Ukraine’s often-thorny investment climate.

“I have been blessed to have very strong companies and people on the executive committee, excellent staff, and a very supportive board of directors,” Williams said.

The USUBC also has a close relationship with the Ukrainian Embassy in Washington, helping Ukraine’s representatives in America establish business and political connections, organize receptions and other events. Currently, a large reception is planned for September to celebrate the 30th anniversary of Ukraine’s independence.

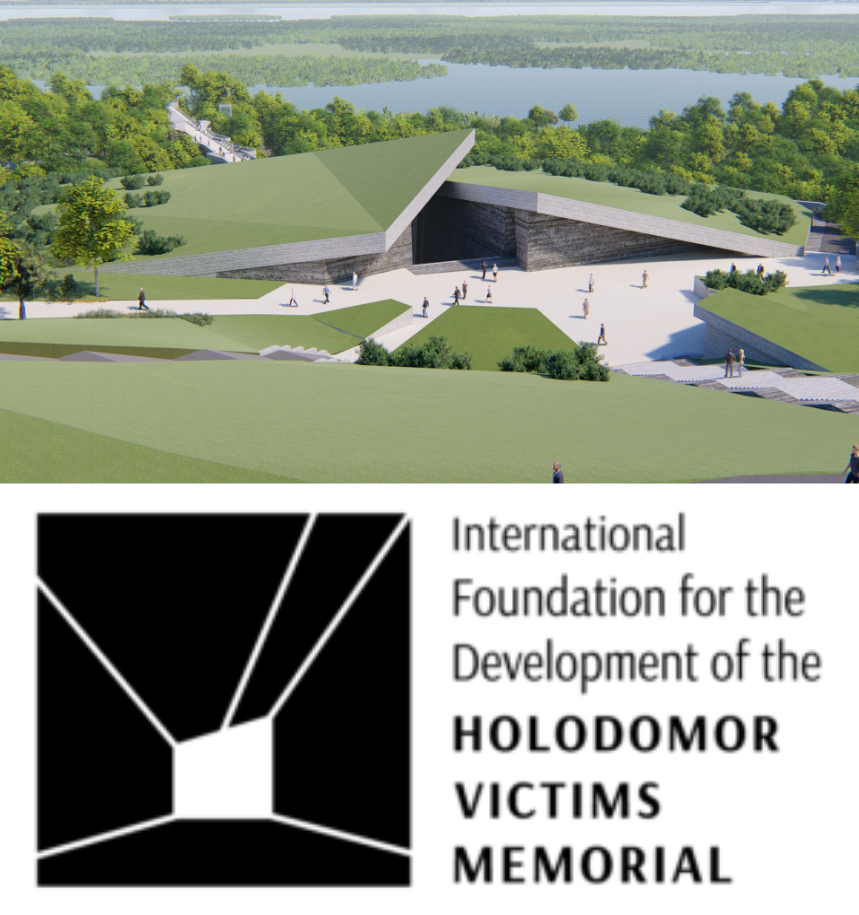

Morgan Williams (L) standing by a model of the new Holodomor Museum at a Holodomor Museum special event on Nov. 19, 2019, in Kyiv. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Battling corruption

Like with other business associations, the USUBC’s biggest battles and achievements involve challenging the pervasive political and business corruption that has held back Ukraine’s economic development and retarded foreign direct investment — still estimated at only $50 billion since 1991.

Williams has been especially focused on combatting periodic attempts by Ukraine’s government to monopolize the agricultural sector, including its exports, for insiders.

“They were always shutting down exports and creating special companies through which exports had to go, creating special taxes for exports,” Williams said. “There were all sorts of people trying to get their hands on money from exporting agricultural products.”

By and large, Williams said, attempts to monopolize the agricultural sector and its exports have failed.

There were other problems, particularly during the rule of Kremlin-backed President Viktor Yanukovych, who fled to Russia during the EuroMaidan Revolution on Feb. 22, 2014. During Yanukovych’s four years in power, for instance, the government refused to repay more than $2 billion in value-added tax refunds, including $800 million to American companies.

Williams said that Ukraine saw progress in solving limited business problems under President Viktor Yushchenko, who served one term from 2005-2010 after voters soundly rejected his reelection bid.

But many of those tentative achievements were reversed by the oligarchy and corrupt interests during Yanukovych’s tenure.

“It wasn’t too long before the old forces, after a year or two, regrouped and again exerted their power,” Williams said.

He said President Petro Poroshenko, in power from 2014-2019, was “pretty easy to work with. He always spoke the right story.”

But Williams said that the presidential records of Yushchenko and Poroshenko — sometimes labeled as pro-Western reformers — never lived up to their pledges.

He believes that attempts by Ukraine’s president since 2019, Volodymyr Zelensky, to curb oligarchs and corruption have been impeded by the same forces that derailed previous efforts. “It’s not so much the presidents as the ingrained system they inherit. It’s just like a great big ball of twine rolled up in chewing gum – so try to unravel that.”

Overall, Ukraine still has a long way to go in restructuring its $160 billion-a-year economy to become modern, prosperous and competitive, citing energy monopolies and an antiquated Ukrzalyznytsia, the state railway, as two examples. The July 1 start of limited agricultural land sales, long supported by the USUBC, is still “a long way from where it needs to go before the land becomes a huge productive asset for Ukraine,” Williams said.

Art curator Lesia Kochergina and Alyona Nevmerzhytska, commercial director of the Kyiv Post, talk to Morgan Williams, president of the U.S.-Ukraine Business Council, at the ArtAsters exhibition in Kyiv on Nov. 12, 2019. (Courtesy of Asters)

Midwestern roots

Williams remains a vigorous advocate for progress and shows no sign of flagging interest in the fight for better bilateral ties between America and Ukraine. He can charm or speak bluntly, depending on what he thinks will work best to advance the goals.

He said the mission of the USUBC remains “keeping Ukrainian business on the agenda in Washington and to keep pounding away at the importance of business development in Ukraine.”

Williams traces his ancestry to Wales, with farming on his father’s side and coal mining on his mother’s side.

During the Great Depression in America, his father dropped music conservatory studies because of a lack of money and switched to business — including for a hardware chain and an insurance company. Work took his father to Ottawa, Kansas, where Williams was born. He remains a Kansan by birth and at heart.

Williams graduated from Ottawa High School in 1957, got a B.A. degree from Ottawa University in Kansas in 1961, and an M.A. degree in economics from the University of Kansas in 1962.

In 1962, Williams managed a farmer’s cooperative union in Plains, Kansas. Four years later, Ottawa University asked him to teach economics and business administration as an associate professor.

His interest in politics had led to him become the chairman of the Republican Party in the Kansas county where he lived. He met prominent Republican Bob Dole, then a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, where he served from 1961 to 1969. Dole later served in the U.S. Senate for 27 years and was the unsuccessful 1996 Republican Party nominee for president.

Williams worked on several of Dole’s election campaigns, first as a volunteer and later as a member of Dole’s staff.

In 1969, Dole helped Williams become the state director of the Kansas Farmers Home Administration, a rural development program providing bank credits to farmers and funding infrastructure projects in rural communities such as housing and water. At 28, he was the youngest person to be appointed to that position and ran the program from Topeka, Kansas, for eight years, until 1977, leading a staff of 300 people.

Williams worked in international economic development on American programs to aid farmers globally and help feed populations in developing countries. He traveled extensively, including to Haiti, India, Egypt, and Indonesia on programs to build cooperative farms around the world.

In 1993, the U.S. government earmarked $800 million in assistance for Ukraine and Russia via the Freedom Support Act. Williams and a business partner won a $60 million, three-year grant to spur private economic development in the agricultural sector of Russia and Ukraine.

The U.S. Agency for International Development-supported program that Williams was working for opened an office in Kyiv in 1993. The program, in 1997, in cooperation with U.S. agribusinesses, created a private agricultural finance corporation to enable Ukrainian farmers to buy American inputs such as seeds, chemicals, and farm machinery. The finance company closed in 1999 because of the financial crisis that started in Russia and spread throughout the region, causing severe financial damage to Ukrainian farms.

Williams later served as president of the Ukraine Market Reform Group before joining SigmaBleyzer.

Holodomor student

He became deeply interested in the Holodomor, Joseph Stalin’s deliberate starvation of 7 million Ukrainians in 1932-1933, shortly after arriving in Ukraine. He had long studied famines.

“You realize the major cause is often corruption: corrupt political systems and politicians who exacerbated a bad situation. One of the ultimate ones, in the 1930s, was caused by Joseph Stalin,” Williams said. He joined forces with American historian, James Mace, who died in 2004, to raise awareness of the Holodomor.

Williams has built up a large collection of artworks related to the Holodomor which has been displayed at various venues and the images are available for anyone to see and use on the USUBC’s website. He serves on the board of directors of the National Holodomor Museum Education Foundation in Chicago.

The USUBC and its members have also supported Ukrainian culture in various spheres such as traditional Ukrainian dancing, choirs, musical groups and orchestras. It has sponsored many cultural events in Ukraine and America, including concerts, and assisted organizations such as the Honchar Folk Art Museum in Kyiv, and the Shevchenko Museum in Kaniv.

Progress and missed opportunities

Although Williams notes the undeniable progress Ukraine has made in its national development since independence, he finds it “perplexing and disappointing” that Ukrainian leaders have squandered so many opportunities to transform their country for the better and that so many have become ensnared in corruption. The corruption threatens national security, especially in light of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war against Ukraine, now in its eighth year and with the Kremlin occupying 7 percent of Ukraine — Crimea and parts of the eastern Donbas.

“The USUBC believes the best defense against Vladimir Putin is to have a strong and growing economy with major reforms,” Williams said. “We also say that the best offensive strategy to keep the EU and the U.S. involved with Ukraine is to have a strong, growing economy with major reforms.”

See also from July 4, 2014: Expats To Watch: Ukraine’s security vaults to No. 1 on business agenda