Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

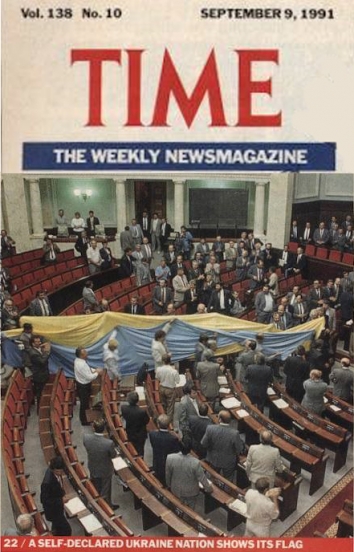

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

WEAKNESS IS LETHAL: WHY PUTIN INVADED UKRAINE

AND HOW THE WAR MUST END

Nataliya Bugayova, Kateryna Stepanenko, and Frederick W. Kagan

Nataliya Bugayova, Kateryna Stepanenko, and Frederick W. Kagan

Institute for the Study of War

Sun, Oct 1, 2023, Washington, D.C.

Russian President Vladimir Putin didn’t invade Ukraine in 2022 because he feared NATO. He invaded because he believed that NATO was weak, that his efforts to regain control of Ukraine by other means had failed, and that installing a pro-Russian government in Kyiv would be safe and easy. His aim was not to defend Russia against some non-existent threat but rather to expand Russia’s power, eradicate Ukraine’s statehood, and destroy NATO, goals he still pursues.

Putin had convinced himself by the end of 2021 that Russia had the opportunity to safely launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine to accomplish two distinct goals: establish Russian control over Ukraine without facing significant Western resistance and break the unity of NATO. Putin has long sought to achieve these goals, but a series of events in 2019-2020 fueled Putin’s belief that he had both the need and a historic opportunity to establish control over Ukraine. Putin’s conviction resulted from the Kremlin’s failed efforts to force Ukraine to submit to Russia’s demands, Putin’s immersion in an ideological and self-reflective bubble during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Western responses to global events and Russian threats in 2021. Putin had decided that he wanted war to achieve his aims by late 2021, and no diplomatic offering from the West or Kyiv short of surrendering to his maximalist demands would have convinced Putin to abandon the historic opportunity he thought he had.

Putin has long tried to accomplish two distinct objectives: breaking up NATO and seizing full control over Ukraine. Putin’s core objectives from the start of his rule have been preserving his regime, establishing an iron grip on Russia domestically, reestablishing Russia as a great power, and forming a multipolar world order in which Russia has a veto over key global events.[1] Establishing control over Ukraine and eroding US influence have always been essential to these core objectives.

Putin has sought to break NATO and Western unity, but not because the Kremlin felt militarily threatened by NATO. Russia’s military posture during Putin’s reign has demonstrated that Putin has never been primarily concerned with the risk of a NATO attack on Russia. Russian military reforms since 2000 have not prioritized creating large mechanized forces on the Russian borders with NATO to defend against invasion.[2] Russia deployed the principal units designed to protect Russia from NATO to Ukraine, which posed no military threat to Russia, in 2021 and 2022.[3] In 2023 - at the height of Russia’s anti-NATO rhetoric - Russia continued to withdraw forces and military equipment from its actual land borders with NATO to support the war in Ukraine.[4] Putin‘s fear of NATO manifested in his preoccupation with the West’s supposed hybrid warfare efforts to stage “color revolutions,” which Russia claimed the West had done in various former Soviet states including Ukraine.[5]

Putin has always been more concerned about the loss of control over Russia’s perceived sphere of influence than about a NATO threat to Russia. Putin’s actual issue with NATO and the West has been that they offered an alternative path to countries that Putin thought fell in Russia’s sphere of influence or even control. The “color revolutions” that so alarmed Putin were, after all, the manifestations of those countries daring to choose the West, or, rather the way of life, governance and values the West represented, over Moscow. NATO and the West threatened Russia by simply existing, promoting their own values, as Russia promoted its values, and being the preferred partner to many former Soviet states – which, in Putin’s view, undermined Russia’s influence over these states. Putin saw the ability to control former Soviet states as an essential prerequisite to reestablishing Russia as a great power, however. In simple terms, the West – and those in the former Soviet states who preferred to partner with the West even without fully breaking with Russia - stood between Putin and what he believed to be Russia’s rightful role in the world.

Putin therefore initiated policies attacking NATO unity and enlargement. Putin has made it a priority throughout his rule to prevent more former Soviet states and even other states, such as the Balkan countries, from joining NATO.[6] The Kremlin has also sought to undermine the relationships between the members of the alliance.[7] Putin accelerated his efforts to undermine Western unity and NATO following the 2014 Euromaidan Revolution that drove out Ukraine’s Russia-friendly president, Viktor Yanukovych, and brought in a pro-Western government. Russia responded by illegally occupying Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine in 2014.

The Russian occupation of Crimea and Donbas in 2014 was driven by Putin’s perception of a need and an opportunity to expand Russia’s power and establish control over Ukraine. The Kremlin sought to preserve strategic naval basing for the Black Sea Fleet in Crimea – an anchor of Russia’s power projection in the region.[8] The Kremlin was concerned that a pro-Western Ukrainian government would end the lease agreement by which Russia had kept the Black Sea Fleet headquartered in Sevastopol. Crimea continues to provide strategic military benefits to Russia. Ukraine is rightfully focused on depriving Russia of these benefits by making Crimea increasingly untenable for the Russian forces.[9] The occupation of Crimea and the Russian invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014 were also a stage of a larger effort to bring a significant portion of Ukraine under Russian control, effectively breaking the country up.[10] Putin perceived a strategic opportunity to do so in the spring of 2014, as Ukraine faced a moment of vulnerability during its government transition after the Euromaidan revolution and as the West was focused on dampening rather than resolving any potential conflict in Ukraine. That effort to establish control over Ukraine failed because Ukrainians, in 2014 as in 2022, proved much more opposed to the idea of Russian overlordship than Putin had expected. Putin’s decisions to invade Ukraine in 2014 and 2022 had a core similarity: in both cases, Putin seized what he thought was an opportunity to realize a long-term goal because he perceived Ukraine and the West to be weak.

Putin allowed his partially successful military intervention to be “frozen” by the Minsk II Accords in February 2015 when it became apparent that he could not achieve all of his aims at the time by force.[11] He secured an important diplomatic victory by getting Russia recognized as a mediator rather than as a party to the conflict in Minsk II despite the fact that Russian military forces had seized Crimea, invaded eastern Ukraine, and remained in both areas actively supporting proxy forces that the Kremlin had stood up and fully controlled. He ensured that Minsk II imposed a series of obligations on Kyiv that gave Russia leverage on Ukrainian politics—and no obligations at all on Russia itself. Minsk II was the diplomatic weapon Putin had created to force Ukraine back into Russia’s orbit when his initial invasion had failed to do so.

Putin turned, in the meantime, to disrupting NATO’s coherence. The Kremlin cultivated a partnership with Hungary - a NATO member - to block resolutions related to Ukraine’s NATO membership.[12] The Kremlin launched a deliberate campaign to coopt Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Putin took advantage of increasingly strained NATO-Turkey relations resulting from conflicting US and Turkish approaches to the Syrian Civil War by engaging Turkey in years-long negotiations to persuade Ankara to purchase Russian S-400 air defense systems – prompting the US to sanction Turkey in 2020.[13] Putin repeatedly used the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline construction project to drive a wedge between the European Union (EU) and the US and appealed to Germany’s economic interests in Europe.[14] Putin sought to benefit from the fact that Germany and France--but not the US or any other NATO states--were parties to the Minsk II accords and then from the “Normandy Format” negotiations to drive wedges between the US on the one hand and Paris and Berlin on the other over the West’s policy toward Russia and Ukraine.[15] Putin fostered divisions among NATO and Western states to ensure that these states would not be united in their response to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine as well as to pursue his larger aim of breaking NATO. His approach had some success in the years leading up to 2022, but not enough to achieve either of his core objectives.

The prospect of Ukrainian NATO membership did not drive Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Russia’s fulminations about a NATO expansion in 2022 were efforts to shape the information space ahead of the invasion, not reactions to NATO’s actions. The first NATO commitment to admitting Ukraine to the alliance came in the 2008 Bucharest Declaration, which promised Ukraine and Georgia paths to membership but took no concrete steps toward opening such paths.[16] Successive annual NATO summits generated no further progress toward membership for either country. Putin intensified the narrative that NATO was a threat to Russia over the years, alleging by 2021 that Russia feared NATO’s imminent expansion in Eastern Europe.[17] NATO had taken no meaningful actions to enlarge at the time, however.[18] Accession of new members to the alliance generally requires that they complete a formal Membership Action Plan (MAP) with specific measures agreed upon by the alliance and the prospective member state. NATO produced no MAP for Ukraine or Georgia, meaning that the formal process for their accession had not even begun.

Read further here: https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/weakness-lethal-why-putin-invaded-ukraine-and-how-war-must-end

NOTE: The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a well known think-tank in Washington, D.C. Natalya Bugayova is from Ukraine and in a previous capacity was the General Manager of the Kyiv Post. She has been in the United States for several years and is a well known analyst and commentator about Putin's war against Ukraine. The following ISW analysis is by Nataliya Bugayova, Kateryna Stepanenko, and Frederick W. Kagan.