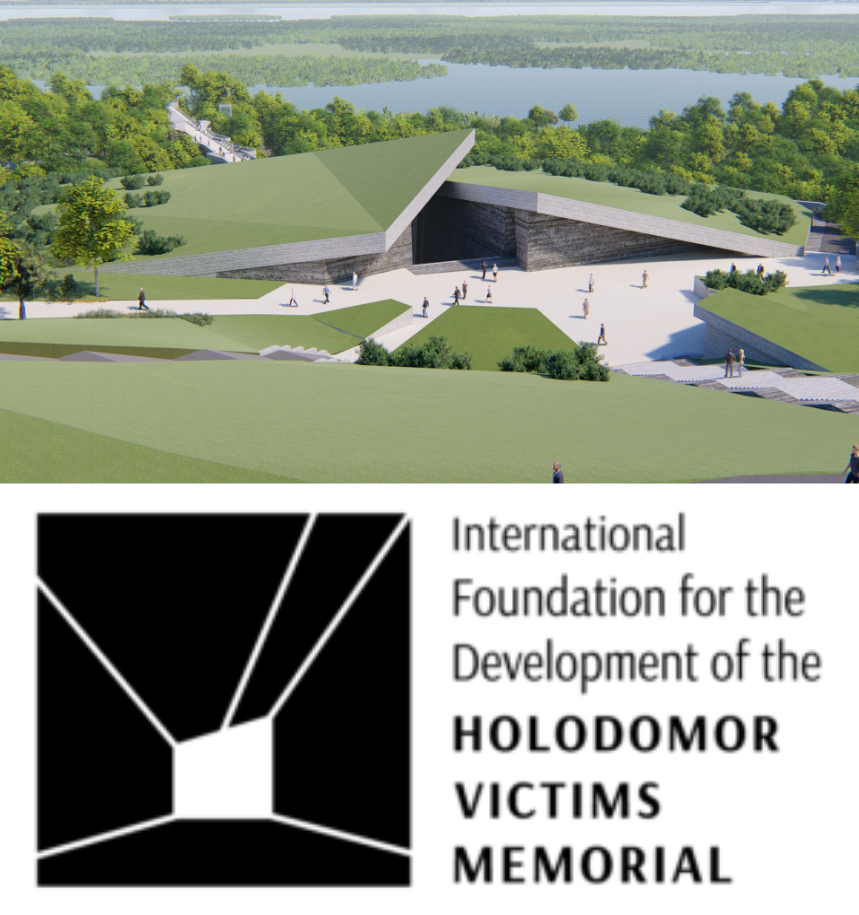

Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

1990 Revolution on Granite: Students’ Strikes

Force Resignation of Prime Minister

.png)

U.S.-Ukraine Foundation, Washington, D.C., Monday, October 18, 2021

By Angela Howard

Student strikes sparking the Revolution on Granite was one of the many important student actions that paved Ukraine’s path to independence and later influenced its choice towards the European democratic values.

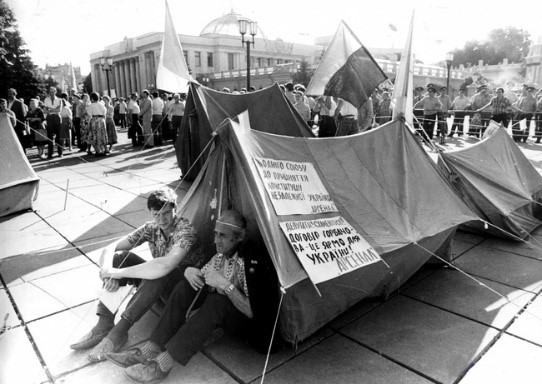

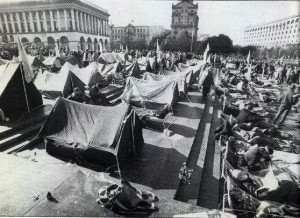

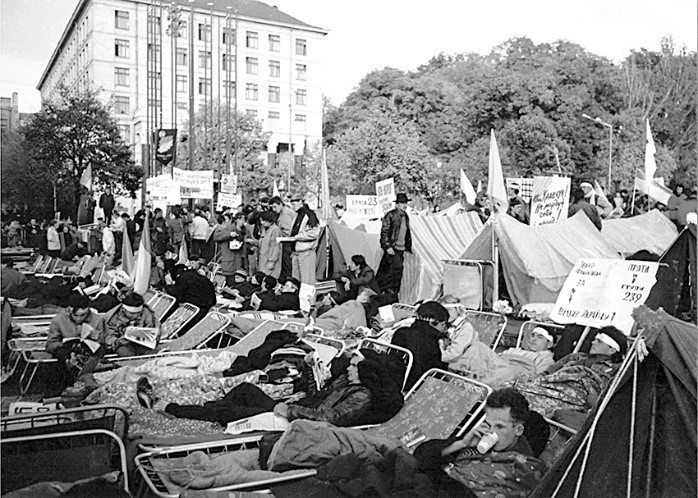

On October 2, 1990, students from across Ukraine gathered in Kyiv on the Square of the October Revolution—now Independence Square (Maidan Nezalezhnosti), the site of the 2014 People’s Revolution of Dignity—to protest Soviet occupation and political imposition. Launching a hunger strike and engaging in acts of civil disobedience through October 17th, the students began one of the most significant movements in the history of Ukrainian independence: the Revolution on Granite. This event would become one of the catalysts for the collapse of the Soviet Union and the birth of a modern Ukraine.

“Effectively, it was [during the Revolution on Granite] that Ukrainian patriotic forces began to enter the field of state-building… the students opted to sit down on granite pavement of the square and it gradually ignited a more fundamental conflict with five demands. Thus, the protesting Ukraine found itself clearly opposed to Soviet Ukraine. The government was forced to respond… it was the student hunger strike that showed that Ukrainians could engage in head-on uncompromising confrontation with the ruling Communist elite. In addition, it showed that such a confrontation could be peaceful and end in political victories.” – Participant, political scientist Serhii Zhyshko

“Effectively, it was [during the Revolution on Granite] that Ukrainian patriotic forces began to enter the field of state-building… the students opted to sit down on granite pavement of the square and it gradually ignited a more fundamental conflict with five demands. Thus, the protesting Ukraine found itself clearly opposed to Soviet Ukraine. The government was forced to respond… it was the student hunger strike that showed that Ukrainians could engage in head-on uncompromising confrontation with the ruling Communist elite. In addition, it showed that such a confrontation could be peaceful and end in political victories.” – Participant, political scientist Serhii Zhyshko

Responding to the looming threat of the proposed Union Treaty (which would strengthen the bonds tying together the republics of the Soviet Union), the students directly and clearly stated their demands: the dismissal of Prime Minister Vitaliy Masol; the hosting of new, multi-party elections in the Ukrainian SSR; abolition of the Union Treaty; legal assurance that Ukrainian military conscripts would serve only within their homeland; and nationalization of Communist Party and Komsomol property.

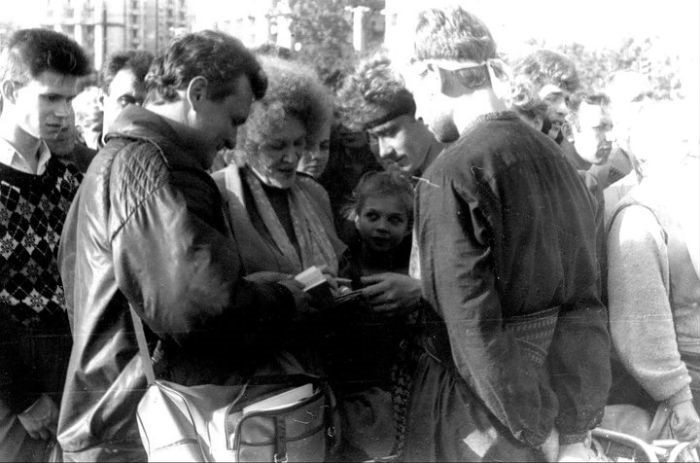

Organized by Oleksandr Serheiivich Donii and lead by the Student Brotherhood and Ukrainian Students Union, the initial core group of student activists on hunger strike numbered 108, not including daily protestors, opposition members of parliament, the support groups providing health checks and proof of the students’ fast, and many, many students who joined the strike throughout the next few weeks. Solidarity grew to about 15,000 people. Strike committees formed in some factories. Thousands of Ukrainians took to the streets to protect the protesting youth. Students outside of Kyiv staged sit-ins at their local universities. A general lack of student attendance brought Ukrainian universities to a standstill, and some even released statements in support of the students.

“We did not expect or hope for this, but there was more support than we could have imagined. It was in small things. Our philosophy teacher was very strict, everyone was afraid of her. And on the exam, she gave me ‘excellent’ and [returned] the credit book with the words: I'm proud of you.”

“We did not expect or hope for this, but there was more support than we could have imagined. It was in small things. Our philosophy teacher was very strict, everyone was afraid of her. And on the exam, she gave me ‘excellent’ and [returned] the credit book with the words: I'm proud of you.”

–Participant, singer and TV presenter, Andzelika Rudnytska

The support of celebrities and leaders, including writer Lina Kostenko, actress Nila Kriukova, science fiction writer Oles Berdnyk, and former political prisoner and MP Stepan Khmara, also drew attention to the cause. Writer Oles Honchar went so far as to publicly burn his Communist Party of the Soviet Union membership card while on the square.

However, the youth also faced many obstacles.

At first, the students’ hunger strike struggled to capture the attention of the country and to endure terrible environmental conditions. Only the fourth day of the hunger strike brought its first TV coverage, and Ukrainians watched the students face down the rain, the unseasonable cold, and hunger. Rukh Secretariat Chairman Mykhailo Horyn described the weather conditions and physical demands as so bad, that he recommended female students not participate. Yet the students (including several girls) persisted.

Many strike coordinators feared the authorities would use physical violence to disband the protestors, though no order to disband the students ever came. Officials appeared to share the perception that abstaining from violence would allow them to wait out the strike while the protests fizzled out. All the same, protestors endured intense mental pressure as they waited for an order that never came, always bearing in mind images of the recent Tiananmen Square crackdowns. Waiting for something to happen, morale began to deteriorate.

Around the tenth day of the hunger strike, the protest reached a low point. With no end in sight, over a week without food, and continuous psychological pressure, many initial participants had to break their fasts. Attempting to set an example and galvanize protestors, certain organizers even joined the hunger

day of the hunger strike, the protest reached a low point. With no end in sight, over a week without food, and continuous psychological pressure, many initial participants had to break their fasts. Attempting to set an example and galvanize protestors, certain organizers even joined the hunger

strike, despite a previous decision that those responsible for leadership and security would not starve.

Yet, despite the setbacks, the youth-led protests continued to grow and draw attention. Toward the end of the seventeen-day hunger strike, activists were turning away those who wanted to join the core hunger strike due to size limitations within the camp.

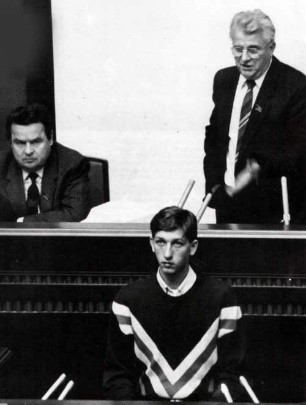

On October 15th, a column of 100,000 protesters broke through the police border near the Verkhovna Rada and representatives from the students were allowed to address the Verkhovna Rada from the parliamentary rostrum. The students made their demands, firmly, and this televised address reached both deputies and people across Ukraine. With public pressure at a new height, officials could no longer ignore the youth’s demands.

“I addressed the highest official, ‘Mr. Leonid,’ not ‘Leonid Makarovich,’ as was customary. Neither the Verkhovna Rada nor the opposition allowed themselves to do so—such an appeal was never broadcast on television. And it was noticeable that he was no longer affected by the demands we made, but by the manner of treatment.” –Organizer, Oleksandr Donii

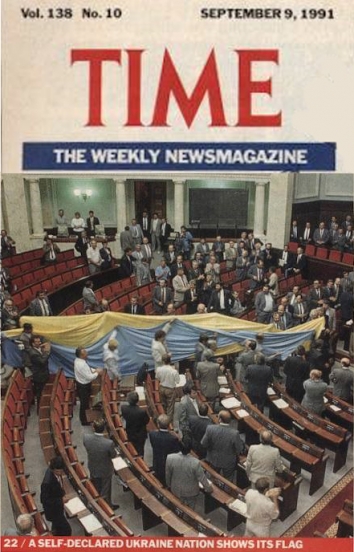

Finally, on October 17th, the Verkhovna Rada adopted a resolution satisfying a several demands of the students and setting the remainder for gradual implementation. The hunger strike ended. Thanks to the youth protests: Vitaly Masol resigned; Ukraine halted the approval of the Union Treaty (despite pressure from Moscow); the Rada codified that Ukrainian conscripts would serve only in the territory of Ukraine; a newly created national commission began to study the possibilities for nationalization of Communist Party and Komsomol property. Though multi-party elections did not come in the spring of 1991, these victories still represented a landmark event: the first time in decades that Ukrainian demonstrators both visibly confronted the authorities and won. Thanks to the courage of the youth, increasing numbers of people began to feel that great change was both possible and on the horizon.

Finally, on October 17th, the Verkhovna Rada adopted a resolution satisfying a several demands of the students and setting the remainder for gradual implementation. The hunger strike ended. Thanks to the youth protests: Vitaly Masol resigned; Ukraine halted the approval of the Union Treaty (despite pressure from Moscow); the Rada codified that Ukrainian conscripts would serve only in the territory of Ukraine; a newly created national commission began to study the possibilities for nationalization of Communist Party and Komsomol property. Though multi-party elections did not come in the spring of 1991, these victories still represented a landmark event: the first time in decades that Ukrainian demonstrators both visibly confronted the authorities and won. Thanks to the courage of the youth, increasing numbers of people began to feel that great change was both possible and on the horizon.

Only nine months later, Ukraine declared its independence as the Soviet Union came to an end.

“I personally know that Ukraine fought. And when they say that Ukraine won independence only because of the non-signing of the Union Treaty and the coup in Moscow — no, that's not true — and our Revolution is a true example... Vyacheslav Chornovil once said the following: ‘Without the Red Route, there would be no ‘Student Hunger Strike,’ and without the ‘Student Hunger Strike,’ there would be no Independence of Ukraine.” –Organizer, Oleksandr Donii

For live footage of the 1990 Revolution on Granite and interviews with its participants recorded in the documentary series “Three Revolutions – Portraits of Ukraine,” click here (https://youtu.be/rnwWkltMc-Y)